*/

We need to stop confusing the public and start conferring the title barrister only on people able to practise here as a barrister. If that leads to a reduction in the number of young people taking the Bar course, it will mean fewer people who have little chance of practice wasting their money, and it will also allow the Inns to focus their finite resources on those most in need of support. That will be good for diversity and for social mobility.

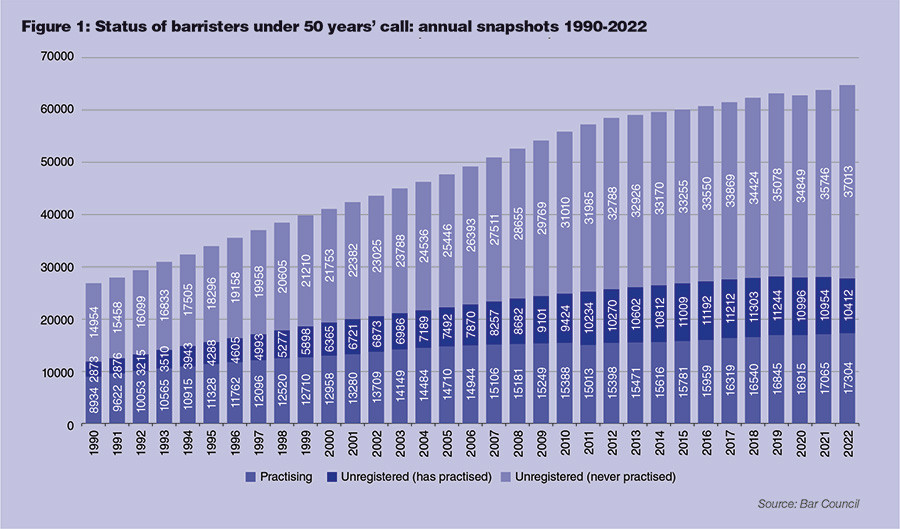

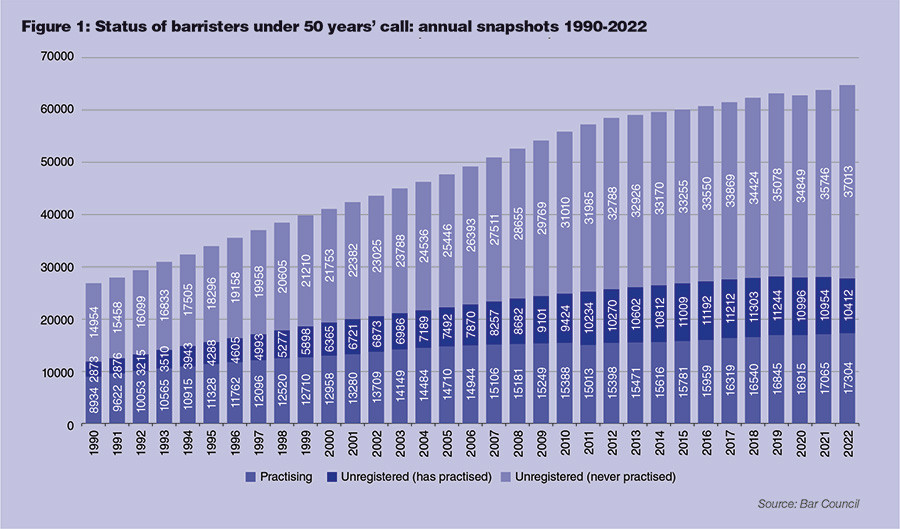

There are about 17,000 or so barristers in England and Wales with a practising certificate, but there are over 70,000 people entitled to say they are a barrister called to the Bar of England and Wales (see Figure 1, below).

At the moment, in order to become a barrister all you have to do is get a qualifying law degree with a 2.2 or better (or convert your degree using a Graduate Diploma), complete ten qualifying sessions with your Inn of Court, and pass the vocational course offered by one of the now ten providers. These are courses which the Bar Standards Board (BSB) permits you to pass in dribs and drabs over no fewer than five years. So, you can become a barrister without ever having practised, and without even having done pupillage, and you can retain that title for life.

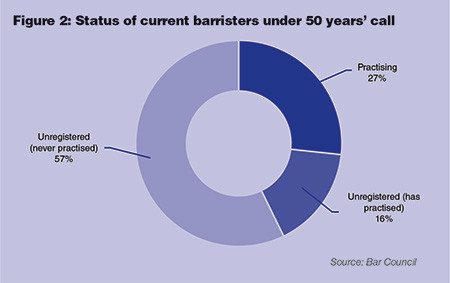

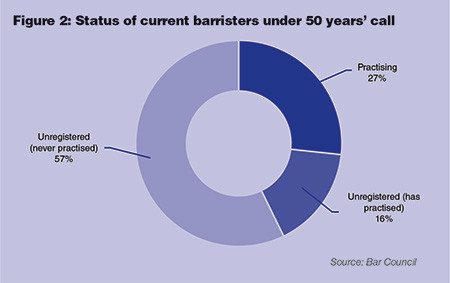

Figure 2 shows a snapshot of our profession now. For every barrister with a practising certificate (PC) there are two who have never been entitled to a PC. And of all the people in the world who are entitled to tell you they are barrister called to the Bar of England and Wales, only 1 in 4 has a practising certificate.

This all creates confusion both for barristers and for the public. A frequent subject of enquiries to the Bar Council’s Ethical Enquiries helpline is what unregistered barristers providing legal services can and cannot say or do. If barristers don’t understand the confusing rules there is no chance that the public will. It also means that the practising Bar has to fund the (ever-more-expensive) BSB which then has to regulate all 70,000+ barristers at the expense of the 17,000. The only way to solve these problems in the long run is to defer call until after pupillage has been obtained, so that the title barrister really means something again.

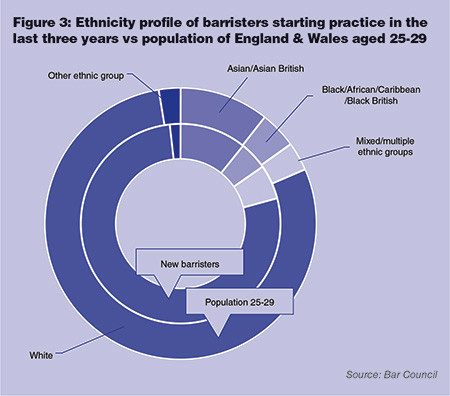

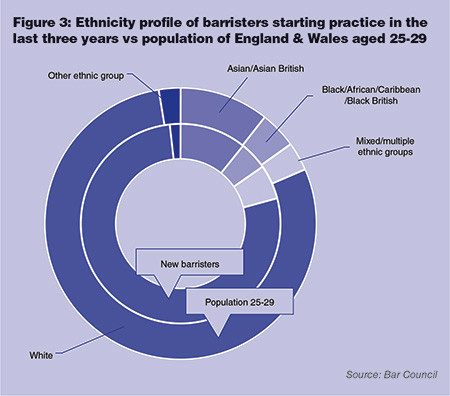

It is worth pausing to see what the intake to the practising Bar looks like in terms of gender and ethnicity, because if (as we think we should) we were to defer call to after pupillage this is the cohort that will form the Bar of the future. For gender the figures for the last three years of entry to the practising Bar are that women very marginally outnumbered men at 51% to 49%. And in terms of ethnicity the statistics are shown in Figure 3.

So, in terms of recruitment to the practising Bar we now have an intake to the Bar that very closely reflects the general population demographic in terms of gender and race. We think that this is important. At the recruitment stage (but certainly not yet in terms of progression and retention), we are well on the way to a race-neutral gender-neutral intake, and therefore on the way to a meritocracy.

We don’t have such a good handle on how the social background of the practising Bar compares with the population as whole. That is partly because it is a difficult thing to measure and partly because when we do ask people questions about their social background not enough people answer. But we suspect we can all agree on two things at least:

We would suggest that we also need to ask ourselves whether we are entirely comfortable that – of those who disclose the relevant information – about 35% of the current intake to the practising Bar is privately educated as against 18% of the A-Level cohort and only 8% of all secondary school pupils.

We are proud that the Bar Council is making contextual recruitment tools available help to identify candidates who have outperformed their immediate peer group, or who have had to overcome particular types of adversity. Such tools can help chambers ensure that they are not missing candidates with great potential who, because of their background, might not yet have achieved quite so highly as contemporaries from a more advantaged background. The Bar Council and Tribepad, who provide the applicant tracking system on which the Pupillage Gateway runs, are going to be working with the company Rare Recruitment to integrate Rare’s extremely impressive and carefully developed contextual recruitment tools. Whether or not to use these tools will be a matter for chambers. Chambers might for instance use it at the stage of inviting people to interview. The cost will be included in the Gateway subscription fee so there will be no separate cost. This won’t be available for the coming round, but it will be ahead of the opening of the 2025 recruitment timetable in late 2024. We really hope there will be a very broad use of these contextual recruitment tools.

How might social mobility be affected if we were to say that people had to have begun pupillage before they were called to the Bar? Some people have told us that they would support deferral of call but for concerns they have about its impact on social mobility. We don’t believe there is any conflict – if we did then we wouldn’t support deferral of call. In fact, we suspect we will be able to do more as a profession to promote social mobility if we do defer call.

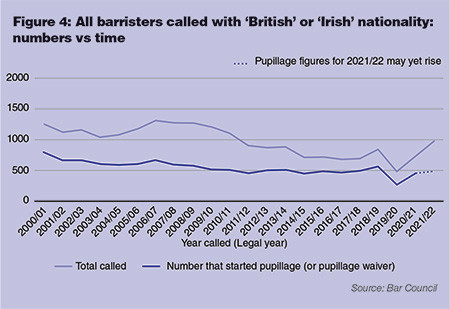

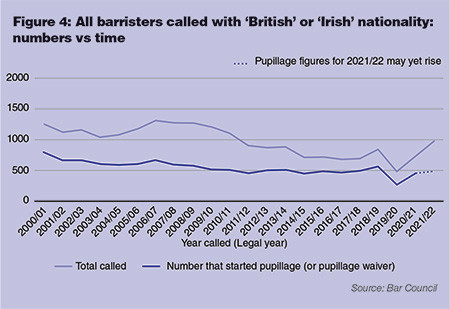

Putting aside for the moment overseas students, many of whom do not intend to practise here, and just stick to students with British or Irish nationality, we see a big difference between the number called and the number who start pupillage (Figure 4). The chance of eventually getting pupillage for British and Irish students is somewhere slightly higher than 1 in 2.

If we defer call, we expect fewer people will do the Bar courses here. It may not be so attractive to overseas students, who may wish to pursue their own domestic routes to practice, especially given that it is no longer the case that call to the Bar of England and Wales enables people to practise without further examinations and/or pupillage locally. Other jurisdictions would need to decide whether to continue to recognise completion of the Bar course as a route to practising entitlements in their own countries. It may also put off some home students.

We believe that some people embark on the Bar course who, in truth, have little prospect of ever securing pupillage. But we suspect they console themselves with the idea that even though they may never be able to practise as a barrister they will become a barrister, nevertheless. If you have a 2.2 you have only about a 1 in 10 chance of securing pupillage but if you pass the Bar course you nevertheless become a barrister (see p 12 of Bar Training 2022 Statistics on enrolment, results, and student progression by course provider, Bar Standards Board Research Team, November 2022). So, we think the present system artificially encourages some people who probably should not be encouraged.

We also believe the present system is likely to discourage some of the young people who do have what it takes and who ought to be encouraged. If you are a really bright, sensible and ambitious 20-something, but with no Bank of Mum and Dad to support you, and you are trying to decide whether to go for the Bar or be a solicitor, we have created a system that makes the Bar looks distinctly unattractive by comparison with becoming a solicitor. So not only do we have a system that sometimes encourages the wrong people, but we fear that we are discouraging some of the best people.

If the impact of deferring call is that there are markedly fewer overseas students, and that the less able domestic students are also put off to some extent, the Inns will be able to focus their finite resources much more closely on those who not only intend to practise here, but who have a real prospect of actually doing so. That, we believe, is the way to improve social mobility. What is needed is focused and sustained support on promising individuals, as opposed to a system which indiscriminately allows almost everyone into the first stage (the Bar course) and then at the next stage (pupillage) cruelly disappoints almost half of those whom we have encouraged to embark on an expensive course, which we are no longer able to restrict to those with a reasonable prospect of success at the Bar.

We need to stop confusing the public and start conferring the title barrister only on people able to practise here as a barrister. If that leads to a reduction in the number of young people taking the Bar course, it will mean fewer people who have little chance of practice wasting their money, and it will also allow the Inns to focus their finite resources on those most in need of support. That will be good for diversity and for social mobility.

There are about 17,000 or so barristers in England and Wales with a practising certificate, but there are over 70,000 people entitled to say they are a barrister called to the Bar of England and Wales (see Figure 1, below).

At the moment, in order to become a barrister all you have to do is get a qualifying law degree with a 2.2 or better (or convert your degree using a Graduate Diploma), complete ten qualifying sessions with your Inn of Court, and pass the vocational course offered by one of the now ten providers. These are courses which the Bar Standards Board (BSB) permits you to pass in dribs and drabs over no fewer than five years. So, you can become a barrister without ever having practised, and without even having done pupillage, and you can retain that title for life.

Figure 2 shows a snapshot of our profession now. For every barrister with a practising certificate (PC) there are two who have never been entitled to a PC. And of all the people in the world who are entitled to tell you they are barrister called to the Bar of England and Wales, only 1 in 4 has a practising certificate.

This all creates confusion both for barristers and for the public. A frequent subject of enquiries to the Bar Council’s Ethical Enquiries helpline is what unregistered barristers providing legal services can and cannot say or do. If barristers don’t understand the confusing rules there is no chance that the public will. It also means that the practising Bar has to fund the (ever-more-expensive) BSB which then has to regulate all 70,000+ barristers at the expense of the 17,000. The only way to solve these problems in the long run is to defer call until after pupillage has been obtained, so that the title barrister really means something again.

It is worth pausing to see what the intake to the practising Bar looks like in terms of gender and ethnicity, because if (as we think we should) we were to defer call to after pupillage this is the cohort that will form the Bar of the future. For gender the figures for the last three years of entry to the practising Bar are that women very marginally outnumbered men at 51% to 49%. And in terms of ethnicity the statistics are shown in Figure 3.

So, in terms of recruitment to the practising Bar we now have an intake to the Bar that very closely reflects the general population demographic in terms of gender and race. We think that this is important. At the recruitment stage (but certainly not yet in terms of progression and retention), we are well on the way to a race-neutral gender-neutral intake, and therefore on the way to a meritocracy.

We don’t have such a good handle on how the social background of the practising Bar compares with the population as whole. That is partly because it is a difficult thing to measure and partly because when we do ask people questions about their social background not enough people answer. But we suspect we can all agree on two things at least:

We would suggest that we also need to ask ourselves whether we are entirely comfortable that – of those who disclose the relevant information – about 35% of the current intake to the practising Bar is privately educated as against 18% of the A-Level cohort and only 8% of all secondary school pupils.

We are proud that the Bar Council is making contextual recruitment tools available help to identify candidates who have outperformed their immediate peer group, or who have had to overcome particular types of adversity. Such tools can help chambers ensure that they are not missing candidates with great potential who, because of their background, might not yet have achieved quite so highly as contemporaries from a more advantaged background. The Bar Council and Tribepad, who provide the applicant tracking system on which the Pupillage Gateway runs, are going to be working with the company Rare Recruitment to integrate Rare’s extremely impressive and carefully developed contextual recruitment tools. Whether or not to use these tools will be a matter for chambers. Chambers might for instance use it at the stage of inviting people to interview. The cost will be included in the Gateway subscription fee so there will be no separate cost. This won’t be available for the coming round, but it will be ahead of the opening of the 2025 recruitment timetable in late 2024. We really hope there will be a very broad use of these contextual recruitment tools.

How might social mobility be affected if we were to say that people had to have begun pupillage before they were called to the Bar? Some people have told us that they would support deferral of call but for concerns they have about its impact on social mobility. We don’t believe there is any conflict – if we did then we wouldn’t support deferral of call. In fact, we suspect we will be able to do more as a profession to promote social mobility if we do defer call.

Putting aside for the moment overseas students, many of whom do not intend to practise here, and just stick to students with British or Irish nationality, we see a big difference between the number called and the number who start pupillage (Figure 4). The chance of eventually getting pupillage for British and Irish students is somewhere slightly higher than 1 in 2.

If we defer call, we expect fewer people will do the Bar courses here. It may not be so attractive to overseas students, who may wish to pursue their own domestic routes to practice, especially given that it is no longer the case that call to the Bar of England and Wales enables people to practise without further examinations and/or pupillage locally. Other jurisdictions would need to decide whether to continue to recognise completion of the Bar course as a route to practising entitlements in their own countries. It may also put off some home students.

We believe that some people embark on the Bar course who, in truth, have little prospect of ever securing pupillage. But we suspect they console themselves with the idea that even though they may never be able to practise as a barrister they will become a barrister, nevertheless. If you have a 2.2 you have only about a 1 in 10 chance of securing pupillage but if you pass the Bar course you nevertheless become a barrister (see p 12 of Bar Training 2022 Statistics on enrolment, results, and student progression by course provider, Bar Standards Board Research Team, November 2022). So, we think the present system artificially encourages some people who probably should not be encouraged.

We also believe the present system is likely to discourage some of the young people who do have what it takes and who ought to be encouraged. If you are a really bright, sensible and ambitious 20-something, but with no Bank of Mum and Dad to support you, and you are trying to decide whether to go for the Bar or be a solicitor, we have created a system that makes the Bar looks distinctly unattractive by comparison with becoming a solicitor. So not only do we have a system that sometimes encourages the wrong people, but we fear that we are discouraging some of the best people.

If the impact of deferring call is that there are markedly fewer overseas students, and that the less able domestic students are also put off to some extent, the Inns will be able to focus their finite resources much more closely on those who not only intend to practise here, but who have a real prospect of actually doing so. That, we believe, is the way to improve social mobility. What is needed is focused and sustained support on promising individuals, as opposed to a system which indiscriminately allows almost everyone into the first stage (the Bar course) and then at the next stage (pupillage) cruelly disappoints almost half of those whom we have encouraged to embark on an expensive course, which we are no longer able to restrict to those with a reasonable prospect of success at the Bar.

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar