*/

Patrick O’Brien and Ben Yong on the changing face of judicial retirement

‘I venture to tell High Court Judges, when I interview them before appointment… that I think they should approach the Bench with the enthusiasm of a bridegroom approaching marriage, or of a priest approaching priesthood.’ (Lord Hailsham, Lord Chancellor 1970: HL Debs 19 November 1970, vol 312 col 1314)

In the past 30 years there has been a sea change in the way judges think about and approach their retirement, and in how the Bar regulates it. The historic approach is exemplified by Lord Hailsham above in his indirect response to the minor scandal caused by a Court of Appeal judge resigning and taking a financial job in the City. The Bench was regarded as a priesthood of a sort – a commitment for life – and a robust constitutional convention barred retired judges from taking on paid legal work and required them to be circumspect about both politics and their time on the Bench. This convention was reinforced by the rules of the Bar Council, which prevented retired judges from practising at the Bar.

Since the mid-1990s this environment has radically changed. The judicial retirement convention is no longer effective. Though it remains part of the intellectual furniture of judges and lawyers, and newly appointed judges sign an ‘understanding’ with the Ministry of Justice about the convention on appointment, no one seems sure what it means and so it cannot be enforced.

Hard regulation – in the form of a Bar Council rule that stated that the Council ‘does not approve …. of former Judges in England and Wales returning to practise in any capacity’ – was removed around 1990. The contemporary Bar Standards Board told us that it does not regard retired judges as a risk and makes no reference to retired judges in its Handbook. The Judiciary of England and Wales has reduced or removed references on the activities of retired judges in successive editions of the Guide to Judicial Conduct.

Prompted initially by the increasing visibility of retired judges in politics and the media in recent years, we began a research project on retired judges (funded by the British Academy/Leverhulme) in 2021. We asked two questions: what do judges do after they retire; and what constraints are they subject to in retirement? To answer this, we created a database of all UK judges appointed to High Court and above between 1950 and 2020 with their appointment and retirement dates. This gave us a sample of 585 judges from England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. We then searched for what they did in retirement – checking Who’s Who, the Dictionary of National Biography, newspaper reports, chambers’ websites, judicial biographies. We also interviewed 21 people, 16 of whom were judges.

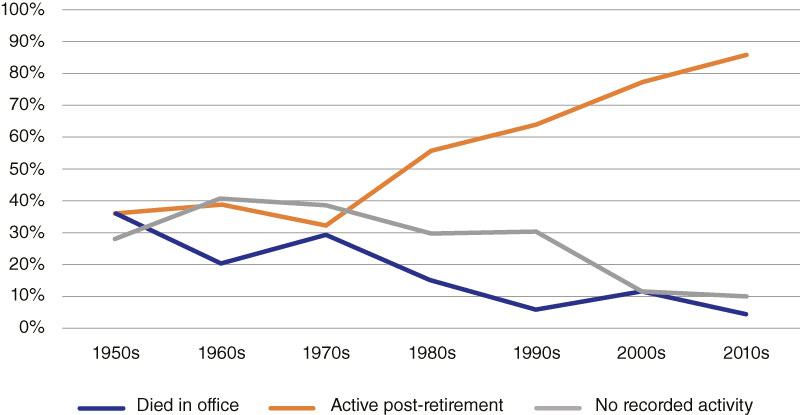

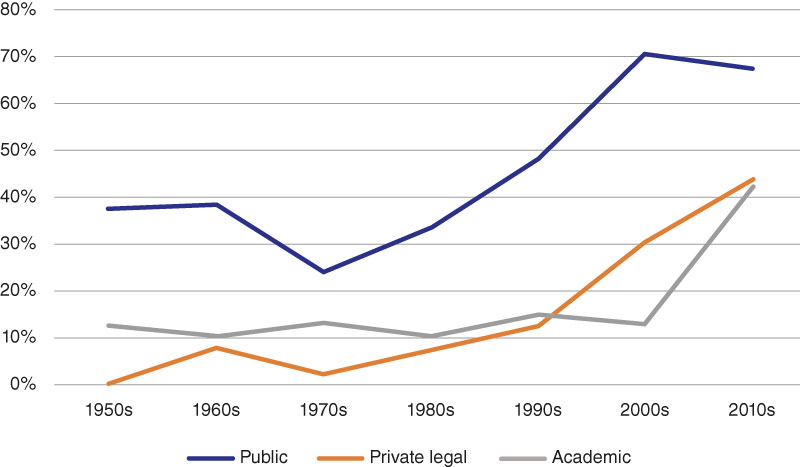

The statistics tell a story. Over time, we can see that the number of judges dying in office, or for whom there is no record of post-retirement activity, falls off dramatically. From the 1970s onwards, post-retirement activity really takes off. By the 2010s, over 85% of judges had some form of traceable activity in retirement (these figures include both voluntary and paid activity). There has been a significant increase in the number of judges with academic affiliations, for example (70% of those in the cohort that retired 2010-20). By 2020, judges were living longer, and retiring earlier, which meant they were more likely to be physically fit for post-retirement work than previous generations.

Figure 1: Judges leaving office 1950-2020

Figure 2: Judicial activity after retirement

The most interesting part of these statistics, however, concerns paid legal work. We divided legal work into two categories, private and public. Public work included matters such as chairing inquiries and acting as a fee-paying judge. The variety of private work, on the other hand, has expanded over the past 30 years: it includes matters such as arbitration and mediation, but also perhaps more controversial work, such as providing legal advice in cases; presiding over mock hearings or benches to coach counsel on style and strategy; and advising private litigation funding companies. In the final 2010-20 cohort, almost 75% of retiring judges took on some form of paid legal role, and it seemed to us that retired members of the senior judiciary (Supreme Court, Court of Appeal) were getting much more of this private legal work than more junior judges.

Based on our interviews and the database, we identify two broad types of judges: ‘priests’ and ‘contractors’. Both types accept the retirement convention, but they interpret it very differently. Priests are circumspect about discussing politics and sceptical about work in retirement, especially where they bring the retired judge close to practice. Contractors, on the other hand, are much more relaxed about discussing politics; and they interpret the prohibition on return to practise very narrowly – as a bar on direct, formal, involvement in litigation. We suggest there has been a broad shift from priests to contractors amongst the UK judiciary. We infer this from the statistical increase in paid legal activity and from our conversations with interviewees.

This divide between priests and contractors has practical consequences. Conventions are non-legal rules of conduct that are defined, redefined and enforced by professional peers – in this case, other judges and retired judges. Very few of our interviewees were able to articulate a basis for the convention, or what counted as a breach. Priests and contractors alike queried the basis and existence of the convention – said one judge: ‘I think everybody is a little uncertain about whether there is actually a rule.’ Moreover, judges were almost unanimous in questioning the legal basis of any form of regulation. Some took the view that judges would just know: ‘What judges need to be told how to behave themselves properly? For goodness’ sake. Grow up.’ Some were more pithy: ‘Do I think there should be regulation? No, because I hate rules.’ And the vast majority of judges we interviewed (both priests and contractors) took the view that retirement activity is solely a matter for the individual judge, even if one might personally disapprove. They were simply unwilling to criticise other retired judges.

To sum up: judges cannot agree upon the basis of the convention or what counts as a breach, or bring themselves to criticise a colleague who appears to be in breach. The only logical conclusion, we feel, is that the convention is dead.

The UK seems to be moving from one of the most restrictive regimes on post-retirement work in the common law world to one of the most permissive. We think this regulatory gap is problematic. There is a legitimate public interest in maintaining the integrity and public standing of the serving judiciary by regulating retired judges. At its most basic, the problem raised is one of bias (or apparent bias). Judges who come close to serving judges or to litigation create a risk of appearance of bias, inappropriate association, or reputational damage to serving judges and the courts. More loosely, sitting judges who express controversial views or do work for overseas regimes with problematic human rights records create risks of association with the judiciary.

Against this, however, we must recognise the fact that retired judges are free agents. They do not and should not expect rules to intrude into their private lives after the Bench. The idea of regulation of former judges for life, irrespective of role or activity, is intrusive and illiberal. For this reason, we conclude that voluntary guidance for retired judges is the best approach, coupled with limited professional regulation. In effect, we believe the historic retirement convention should be revived and updated. The Judiciary should provide more detailed and robust voluntary guidance to retired judges on how to respect the convention and avoid creating risks of bias or association that might affect the serving judiciary.

When it comes to professional legal work, we believe that more is required. There are two spheres of activity that require attention. The first concerns judges seeking post retirement work while still on the Bench. That really does risk appearance of bias. The second, more difficult, scenario is where former judges have returned to practice. Interviewees often made a distinction between advocacy in court and other kinds of legal service – legal advice and consultancy. The former was seen as unacceptable by most interviewees; the latter was just fine. But, as one interviewee put it to us:

In any real sense, they’ve gone back to practice… they’ve got their names outside chambers. You ring their clerk if you want them. How is that not going back to practice?

We agree. Although the services provided are often unregulated, former judges who offer legal services in this way have ‘returned to practice’ in any meaningful socially understood sense of the term – and they will be perceived by reasonable members of the public as having done so. Here we are particularly thinking of matters like paid legal advice, court advocacy; but also those that draw on ‘insider information’, such as providing training or mock trial work. For the most part, retired judges provide unregulated legal services without a practising certificate.

In common with most of our interviewees, we do not think there is anything inherently wrong with judges returning to practice in some capacity. Given increases in lifespan and the modern tendency to recruit judges at a relatively young age, we see some positives. As a former judge memorably and emotionally put it to us in a seminar, for some people the Bench will represent a wrong professional turn and it is too much to expect them to grin and bear that mistake for decades. Thus, in this context we believe that, in addition to detailed advice provided by the Judiciary on the matter, the Ministry of Justice understanding and the England and Wales Guide to Judicial Conduct should be revised to make clear it is acceptable for retired judges to return to practice, but that returning judges should obtain a practising certificate from either the Bar Standards Board or the Solicitors Regulation Authority. In effect, a revived convention should require retired judges to ‘opt-in’ to professional regulation. In addition, the BSB and SRA should provide dedicated rules for former judges in practice, including appropriate practice restrictions.

Those are our suggestions. But process matters. Whatever is decided needs to done in consultation with the key stakeholders: the legal professions, the Ministry of Justice, the professional regulators, and above all, the Judiciary. Given the evident hostility of judges to regulation in this area, if there is no buy-in from them, any attempt at reform will fail.

To find out more, see the Judicial Afterlife project website.

‘I venture to tell High Court Judges, when I interview them before appointment… that I think they should approach the Bench with the enthusiasm of a bridegroom approaching marriage, or of a priest approaching priesthood.’ (Lord Hailsham, Lord Chancellor 1970: HL Debs 19 November 1970, vol 312 col 1314)

In the past 30 years there has been a sea change in the way judges think about and approach their retirement, and in how the Bar regulates it. The historic approach is exemplified by Lord Hailsham above in his indirect response to the minor scandal caused by a Court of Appeal judge resigning and taking a financial job in the City. The Bench was regarded as a priesthood of a sort – a commitment for life – and a robust constitutional convention barred retired judges from taking on paid legal work and required them to be circumspect about both politics and their time on the Bench. This convention was reinforced by the rules of the Bar Council, which prevented retired judges from practising at the Bar.

Since the mid-1990s this environment has radically changed. The judicial retirement convention is no longer effective. Though it remains part of the intellectual furniture of judges and lawyers, and newly appointed judges sign an ‘understanding’ with the Ministry of Justice about the convention on appointment, no one seems sure what it means and so it cannot be enforced.

Hard regulation – in the form of a Bar Council rule that stated that the Council ‘does not approve …. of former Judges in England and Wales returning to practise in any capacity’ – was removed around 1990. The contemporary Bar Standards Board told us that it does not regard retired judges as a risk and makes no reference to retired judges in its Handbook. The Judiciary of England and Wales has reduced or removed references on the activities of retired judges in successive editions of the Guide to Judicial Conduct.

Prompted initially by the increasing visibility of retired judges in politics and the media in recent years, we began a research project on retired judges (funded by the British Academy/Leverhulme) in 2021. We asked two questions: what do judges do after they retire; and what constraints are they subject to in retirement? To answer this, we created a database of all UK judges appointed to High Court and above between 1950 and 2020 with their appointment and retirement dates. This gave us a sample of 585 judges from England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. We then searched for what they did in retirement – checking Who’s Who, the Dictionary of National Biography, newspaper reports, chambers’ websites, judicial biographies. We also interviewed 21 people, 16 of whom were judges.

The statistics tell a story. Over time, we can see that the number of judges dying in office, or for whom there is no record of post-retirement activity, falls off dramatically. From the 1970s onwards, post-retirement activity really takes off. By the 2010s, over 85% of judges had some form of traceable activity in retirement (these figures include both voluntary and paid activity). There has been a significant increase in the number of judges with academic affiliations, for example (70% of those in the cohort that retired 2010-20). By 2020, judges were living longer, and retiring earlier, which meant they were more likely to be physically fit for post-retirement work than previous generations.

Figure 1: Judges leaving office 1950-2020

Figure 2: Judicial activity after retirement

The most interesting part of these statistics, however, concerns paid legal work. We divided legal work into two categories, private and public. Public work included matters such as chairing inquiries and acting as a fee-paying judge. The variety of private work, on the other hand, has expanded over the past 30 years: it includes matters such as arbitration and mediation, but also perhaps more controversial work, such as providing legal advice in cases; presiding over mock hearings or benches to coach counsel on style and strategy; and advising private litigation funding companies. In the final 2010-20 cohort, almost 75% of retiring judges took on some form of paid legal role, and it seemed to us that retired members of the senior judiciary (Supreme Court, Court of Appeal) were getting much more of this private legal work than more junior judges.

Based on our interviews and the database, we identify two broad types of judges: ‘priests’ and ‘contractors’. Both types accept the retirement convention, but they interpret it very differently. Priests are circumspect about discussing politics and sceptical about work in retirement, especially where they bring the retired judge close to practice. Contractors, on the other hand, are much more relaxed about discussing politics; and they interpret the prohibition on return to practise very narrowly – as a bar on direct, formal, involvement in litigation. We suggest there has been a broad shift from priests to contractors amongst the UK judiciary. We infer this from the statistical increase in paid legal activity and from our conversations with interviewees.

This divide between priests and contractors has practical consequences. Conventions are non-legal rules of conduct that are defined, redefined and enforced by professional peers – in this case, other judges and retired judges. Very few of our interviewees were able to articulate a basis for the convention, or what counted as a breach. Priests and contractors alike queried the basis and existence of the convention – said one judge: ‘I think everybody is a little uncertain about whether there is actually a rule.’ Moreover, judges were almost unanimous in questioning the legal basis of any form of regulation. Some took the view that judges would just know: ‘What judges need to be told how to behave themselves properly? For goodness’ sake. Grow up.’ Some were more pithy: ‘Do I think there should be regulation? No, because I hate rules.’ And the vast majority of judges we interviewed (both priests and contractors) took the view that retirement activity is solely a matter for the individual judge, even if one might personally disapprove. They were simply unwilling to criticise other retired judges.

To sum up: judges cannot agree upon the basis of the convention or what counts as a breach, or bring themselves to criticise a colleague who appears to be in breach. The only logical conclusion, we feel, is that the convention is dead.

The UK seems to be moving from one of the most restrictive regimes on post-retirement work in the common law world to one of the most permissive. We think this regulatory gap is problematic. There is a legitimate public interest in maintaining the integrity and public standing of the serving judiciary by regulating retired judges. At its most basic, the problem raised is one of bias (or apparent bias). Judges who come close to serving judges or to litigation create a risk of appearance of bias, inappropriate association, or reputational damage to serving judges and the courts. More loosely, sitting judges who express controversial views or do work for overseas regimes with problematic human rights records create risks of association with the judiciary.

Against this, however, we must recognise the fact that retired judges are free agents. They do not and should not expect rules to intrude into their private lives after the Bench. The idea of regulation of former judges for life, irrespective of role or activity, is intrusive and illiberal. For this reason, we conclude that voluntary guidance for retired judges is the best approach, coupled with limited professional regulation. In effect, we believe the historic retirement convention should be revived and updated. The Judiciary should provide more detailed and robust voluntary guidance to retired judges on how to respect the convention and avoid creating risks of bias or association that might affect the serving judiciary.

When it comes to professional legal work, we believe that more is required. There are two spheres of activity that require attention. The first concerns judges seeking post retirement work while still on the Bench. That really does risk appearance of bias. The second, more difficult, scenario is where former judges have returned to practice. Interviewees often made a distinction between advocacy in court and other kinds of legal service – legal advice and consultancy. The former was seen as unacceptable by most interviewees; the latter was just fine. But, as one interviewee put it to us:

In any real sense, they’ve gone back to practice… they’ve got their names outside chambers. You ring their clerk if you want them. How is that not going back to practice?

We agree. Although the services provided are often unregulated, former judges who offer legal services in this way have ‘returned to practice’ in any meaningful socially understood sense of the term – and they will be perceived by reasonable members of the public as having done so. Here we are particularly thinking of matters like paid legal advice, court advocacy; but also those that draw on ‘insider information’, such as providing training or mock trial work. For the most part, retired judges provide unregulated legal services without a practising certificate.

In common with most of our interviewees, we do not think there is anything inherently wrong with judges returning to practice in some capacity. Given increases in lifespan and the modern tendency to recruit judges at a relatively young age, we see some positives. As a former judge memorably and emotionally put it to us in a seminar, for some people the Bench will represent a wrong professional turn and it is too much to expect them to grin and bear that mistake for decades. Thus, in this context we believe that, in addition to detailed advice provided by the Judiciary on the matter, the Ministry of Justice understanding and the England and Wales Guide to Judicial Conduct should be revised to make clear it is acceptable for retired judges to return to practice, but that returning judges should obtain a practising certificate from either the Bar Standards Board or the Solicitors Regulation Authority. In effect, a revived convention should require retired judges to ‘opt-in’ to professional regulation. In addition, the BSB and SRA should provide dedicated rules for former judges in practice, including appropriate practice restrictions.

Those are our suggestions. But process matters. Whatever is decided needs to done in consultation with the key stakeholders: the legal professions, the Ministry of Justice, the professional regulators, and above all, the Judiciary. Given the evident hostility of judges to regulation in this area, if there is no buy-in from them, any attempt at reform will fail.

To find out more, see the Judicial Afterlife project website.

Patrick O’Brien and Ben Yong on the changing face of judicial retirement

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar