*/

On 14 August 2024 Judge Everett, the Recorder of Chester, sentenced Julie Sweeney to 15 months’ imprisonment for posting a comment on Facebook that said: ‘It’s absolutely ridiculous. Don’t protect the mosques. Blow the mosque up with the adults in it.’ The message would have been read by very many people.

In the Daily Telegraph on 15 August 2024 Lord Frost, apparently seriously, wrote:

‘Of course we all agree that rioting and violence should be punished. We all agree that threats and – genuine, meaningful – incitement to violence are not covered by the right to free speech. Many of those punished in recent days have been convicted for exactly those things. But not all have. We shouldn’t be surprised by that. For our legislation goes much wider than that, to criminalise far wider categories of speech and messaging. It’s now being used, brutally, by a government that has little real regard for free speech.’

It is quite difficult to know where to start with this. One could mention, first, that the offence in question – publishing threatening, abusive or insulting written material with the intention of stirring up racial hatred – was enacted during the second Thatcher administration (not now remembered for its liberal instincts) in 1986 as s 19 of the Public Order Act of that year. It carries a maximum sentence of seven years’ imprisonment.

It has remained on the statute book unaltered in the 38 years since then, 25 of which were under Conservative rule. In that period people have been charged, convicted and sentenced under that section without anyone suggesting, until now, that to do so jeopardised the right to free speech. So far as I am aware, no legislator has ever suggested during those 38 years that s 19 should be amended (let alone repealed) on the ground that it represented a potential threat to freedom of speech.

One could point out, as Lord Frost appears grudgingly to concede, that the right to free speech in Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights is qualified, and not absolute (indeed, apart from the right not to be tortured all the rights are qualified). It states:

‘Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers. … The exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary.’

It is not too difficult to see that in our democratic society the criminalisation of a statement placed on Facebook advocating that a Mosque filled with worshippers should be ‘blown up’ is plainly necessary in the interests of public safety and for the prevention of disorder and crime and for the protection of health and morals.

Ms Sweeney must be taken to have recognised all this and to have accepted that her words crossed the line, because she pleaded guilty.

One could mention that the sentencing guidelines for this offence, formulated by the independent Sentencing Council pursuant to the terms of the Sentencing Act 2020, (enacted during the second Johnson administration) suggest a starting point of one to three years’ immediate imprisonment depending on culpability and the harm caused. A discount of one-third for a guilty plea and a further discount for no previous convictions would suggest that in this case a starting point of two years was used, which lies exactly in the middle of the bracket.

One could mention that the prosecutor’s decision to charge the defendant under s 19, and the sentence handed down by the judge, had absolutely nothing to do with the government. Lord Frost’s statement that this legislation is ‘being used, brutally, by a government that has little real regard for free speech’ is, putting it as politely as I can, untenable. Judge Everett no doubt would have heard Ministers saying repeatedly that rioters would ‘face the full force of the law’. But that would not have had the slightest influence on the discharge by him of his duty under his judicial oath ‘to do right to all manner of people after the laws and usages of this realm, without fear or favour, affection or ill will’.

The only question in my mind, given the seriously menacing language used, is why Judge Everett took as his starting point a mere two years’ imprisonment. I am struggling to imagine what worse language the Sentencing Council had in mind which would give rise to a starting point of three years’ imprisonment – the top of the bracket (but which is, after all, not even half of the maximum sentence).

In my opinion, Ms Sweeney can count herself fortunate that she was not charged under s 44 of the Serious Crime Act 2007 with intentionally encouraging or assisting an offence. These offences replaced and clarified some old, long-standing, common law incitement offences. Make no mistake, inciting others to commit crimes has been a serious criminal offence for a very long time.

It is plausible that, in the words of s 44, by her post Ms Sweeney (a) did an act which was capable of encouraging the commission of the offence of murder; and (b) she intended to encourage its commission. If she had been thus charged and found guilty, she would have been sentenced to life imprisonment under s 58(2).* That is not a maximum sentence, but the singular available sentence.

Clearly, riot-supporting keyboard warriors should think twice before firing their opinions into the ether. As Ms Sweeney has discovered under s 19 of the 1986 Act, the line between legitimate free speech and criminal hate speech is, rightly, a fine one. The classification turns on whether the speech is intended to stir up racial hatred or has that effect.

Section 19 was not designed by its framers merely to deter the infliction of individual suffering but was also, no doubt, intended to promote inter-racial harmony generally. As such, there is no reason either to change it or to interfere with the use that prosecutors make of it.

This important topic was discussed with Baroness Helena Kennedy and Lord Falconer in our podcast Law & Disorder (listen to our most recent bonus episode released on 7 August 2024). In it I complained that there has not been enough public information put out concerning the crimes offenders might be charged with and what sentences under the guidelines they might face if found guilty.

Helena explained that under the doctrine of separation of powers it would not be appropriate for the government to be giving out that information. Rather, she suggested that the information should be disseminated by retired judges like me!

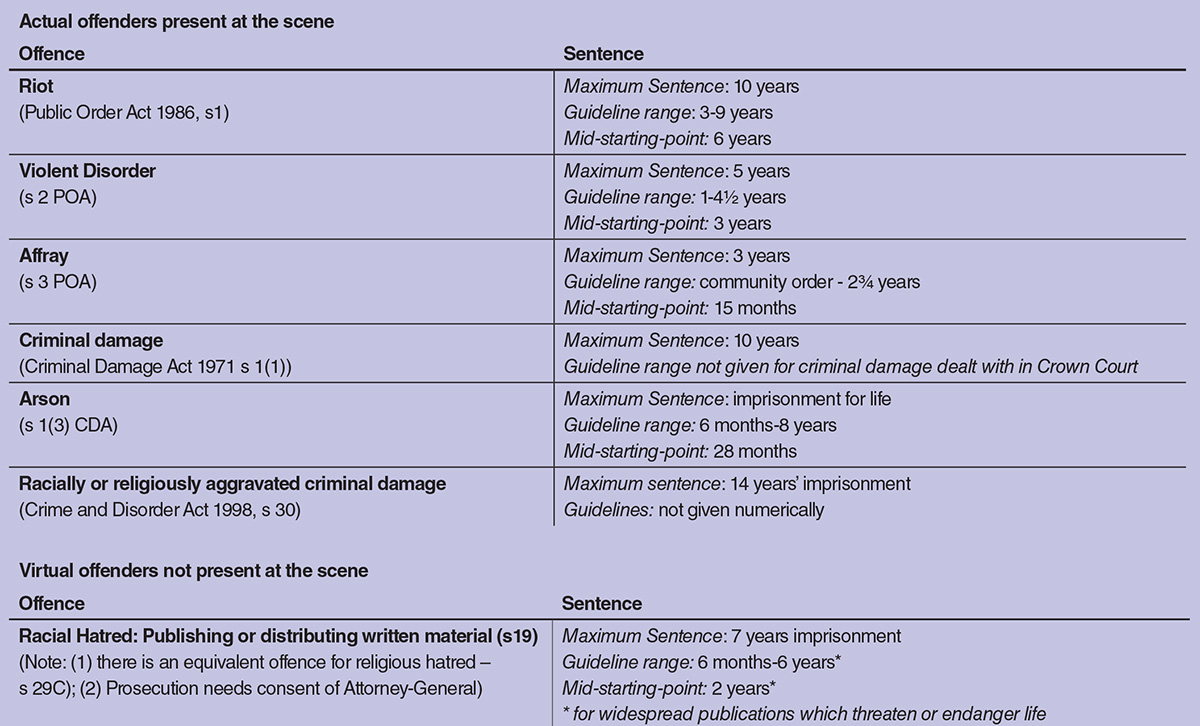

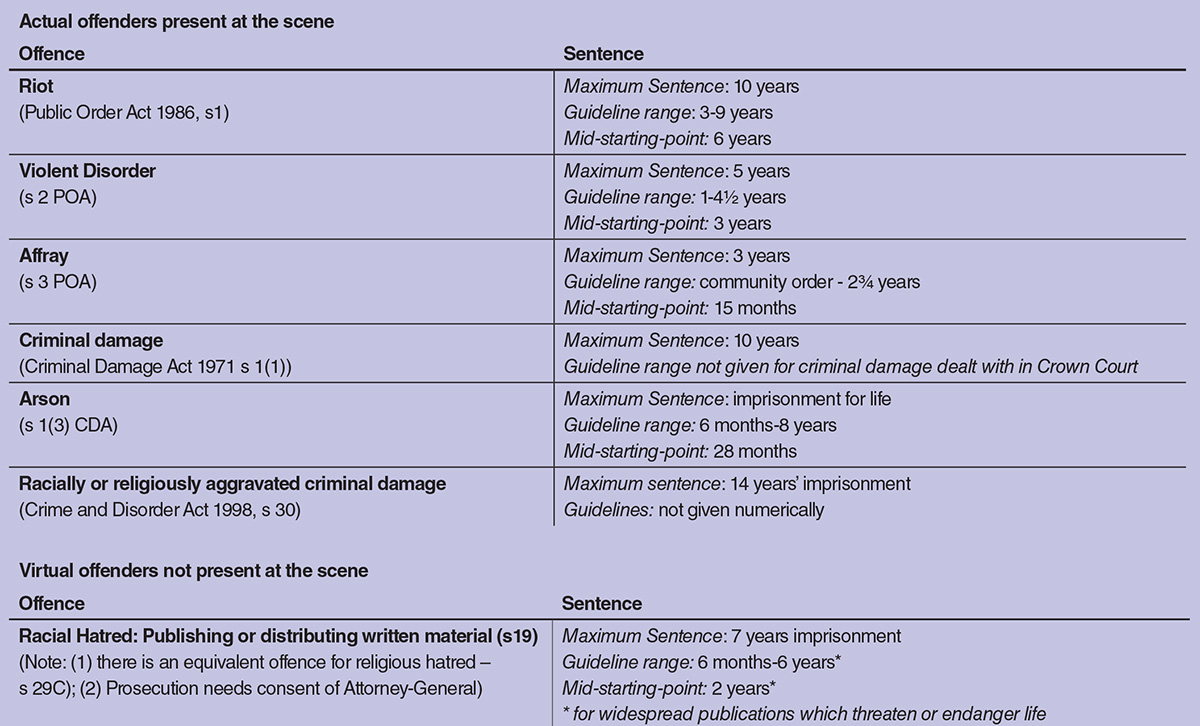

I therefore set out below (see box) the range of the mainstream serious offences triable on indictment for each category, and the indicated sentencing guidelines.

At the time of writing, a question often asked is why most offenders appearing in court have been charged with (and pleaded guilty to) the lesser offence of violent disorder rather than the more serious offence of riot. The only material difference between the two offences is the number of participants. Violent disorder can be committed where there are as few as three participants. Riot needs at least 12. It is obvious that the majority, if not all, of the arrested offenders, were actually taking part in a riot with at least 12 participants. So why have they not been charged with riot? Why have the courts’ hands been tied to the lesser maximum sentence of five years?

I suspect that the charging of the lesser offence represents a form of tacit plea bargain whereby the defendant will accept and plead guilty to that lesser offence thereby allowing the court to deal with it expeditiously with the highly desirable, seemingly effective, concomitant deterrent effect.

Subscribe to the Law & Disorder podcast with Sir Nicholas Mostyn, Baroness Helena Kennedy KC and Lord Charlie Falconer

Offence and sentence

Notes

*This article has been updated to correct a typographical error. The reference to s 58(5) was changed to s 58(2).

On 14 August 2024 Judge Everett, the Recorder of Chester, sentenced Julie Sweeney to 15 months’ imprisonment for posting a comment on Facebook that said: ‘It’s absolutely ridiculous. Don’t protect the mosques. Blow the mosque up with the adults in it.’ The message would have been read by very many people.

In the Daily Telegraph on 15 August 2024 Lord Frost, apparently seriously, wrote:

‘Of course we all agree that rioting and violence should be punished. We all agree that threats and – genuine, meaningful – incitement to violence are not covered by the right to free speech. Many of those punished in recent days have been convicted for exactly those things. But not all have. We shouldn’t be surprised by that. For our legislation goes much wider than that, to criminalise far wider categories of speech and messaging. It’s now being used, brutally, by a government that has little real regard for free speech.’

It is quite difficult to know where to start with this. One could mention, first, that the offence in question – publishing threatening, abusive or insulting written material with the intention of stirring up racial hatred – was enacted during the second Thatcher administration (not now remembered for its liberal instincts) in 1986 as s 19 of the Public Order Act of that year. It carries a maximum sentence of seven years’ imprisonment.

It has remained on the statute book unaltered in the 38 years since then, 25 of which were under Conservative rule. In that period people have been charged, convicted and sentenced under that section without anyone suggesting, until now, that to do so jeopardised the right to free speech. So far as I am aware, no legislator has ever suggested during those 38 years that s 19 should be amended (let alone repealed) on the ground that it represented a potential threat to freedom of speech.

One could point out, as Lord Frost appears grudgingly to concede, that the right to free speech in Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights is qualified, and not absolute (indeed, apart from the right not to be tortured all the rights are qualified). It states:

‘Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers. … The exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary.’

It is not too difficult to see that in our democratic society the criminalisation of a statement placed on Facebook advocating that a Mosque filled with worshippers should be ‘blown up’ is plainly necessary in the interests of public safety and for the prevention of disorder and crime and for the protection of health and morals.

Ms Sweeney must be taken to have recognised all this and to have accepted that her words crossed the line, because she pleaded guilty.

One could mention that the sentencing guidelines for this offence, formulated by the independent Sentencing Council pursuant to the terms of the Sentencing Act 2020, (enacted during the second Johnson administration) suggest a starting point of one to three years’ immediate imprisonment depending on culpability and the harm caused. A discount of one-third for a guilty plea and a further discount for no previous convictions would suggest that in this case a starting point of two years was used, which lies exactly in the middle of the bracket.

One could mention that the prosecutor’s decision to charge the defendant under s 19, and the sentence handed down by the judge, had absolutely nothing to do with the government. Lord Frost’s statement that this legislation is ‘being used, brutally, by a government that has little real regard for free speech’ is, putting it as politely as I can, untenable. Judge Everett no doubt would have heard Ministers saying repeatedly that rioters would ‘face the full force of the law’. But that would not have had the slightest influence on the discharge by him of his duty under his judicial oath ‘to do right to all manner of people after the laws and usages of this realm, without fear or favour, affection or ill will’.

The only question in my mind, given the seriously menacing language used, is why Judge Everett took as his starting point a mere two years’ imprisonment. I am struggling to imagine what worse language the Sentencing Council had in mind which would give rise to a starting point of three years’ imprisonment – the top of the bracket (but which is, after all, not even half of the maximum sentence).

In my opinion, Ms Sweeney can count herself fortunate that she was not charged under s 44 of the Serious Crime Act 2007 with intentionally encouraging or assisting an offence. These offences replaced and clarified some old, long-standing, common law incitement offences. Make no mistake, inciting others to commit crimes has been a serious criminal offence for a very long time.

It is plausible that, in the words of s 44, by her post Ms Sweeney (a) did an act which was capable of encouraging the commission of the offence of murder; and (b) she intended to encourage its commission. If she had been thus charged and found guilty, she would have been sentenced to life imprisonment under s 58(2).* That is not a maximum sentence, but the singular available sentence.

Clearly, riot-supporting keyboard warriors should think twice before firing their opinions into the ether. As Ms Sweeney has discovered under s 19 of the 1986 Act, the line between legitimate free speech and criminal hate speech is, rightly, a fine one. The classification turns on whether the speech is intended to stir up racial hatred or has that effect.

Section 19 was not designed by its framers merely to deter the infliction of individual suffering but was also, no doubt, intended to promote inter-racial harmony generally. As such, there is no reason either to change it or to interfere with the use that prosecutors make of it.

This important topic was discussed with Baroness Helena Kennedy and Lord Falconer in our podcast Law & Disorder (listen to our most recent bonus episode released on 7 August 2024). In it I complained that there has not been enough public information put out concerning the crimes offenders might be charged with and what sentences under the guidelines they might face if found guilty.

Helena explained that under the doctrine of separation of powers it would not be appropriate for the government to be giving out that information. Rather, she suggested that the information should be disseminated by retired judges like me!

I therefore set out below (see box) the range of the mainstream serious offences triable on indictment for each category, and the indicated sentencing guidelines.

At the time of writing, a question often asked is why most offenders appearing in court have been charged with (and pleaded guilty to) the lesser offence of violent disorder rather than the more serious offence of riot. The only material difference between the two offences is the number of participants. Violent disorder can be committed where there are as few as three participants. Riot needs at least 12. It is obvious that the majority, if not all, of the arrested offenders, were actually taking part in a riot with at least 12 participants. So why have they not been charged with riot? Why have the courts’ hands been tied to the lesser maximum sentence of five years?

I suspect that the charging of the lesser offence represents a form of tacit plea bargain whereby the defendant will accept and plead guilty to that lesser offence thereby allowing the court to deal with it expeditiously with the highly desirable, seemingly effective, concomitant deterrent effect.

Subscribe to the Law & Disorder podcast with Sir Nicholas Mostyn, Baroness Helena Kennedy KC and Lord Charlie Falconer

Offence and sentence

Notes

*This article has been updated to correct a typographical error. The reference to s 58(5) was changed to s 58(2).

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar