*/

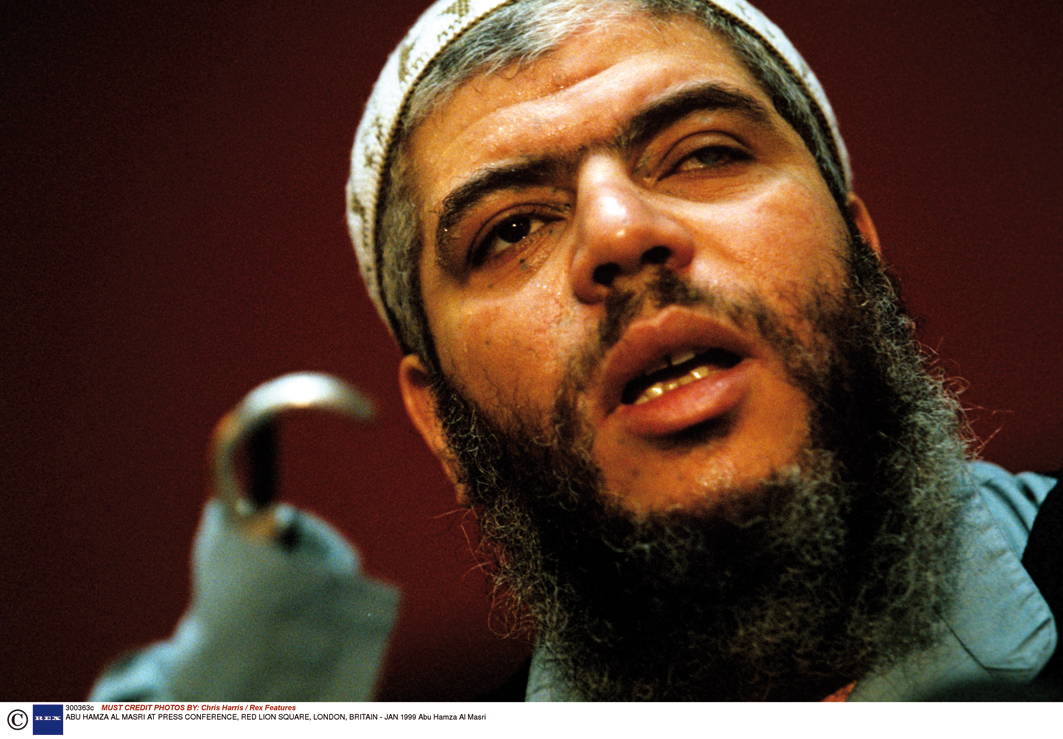

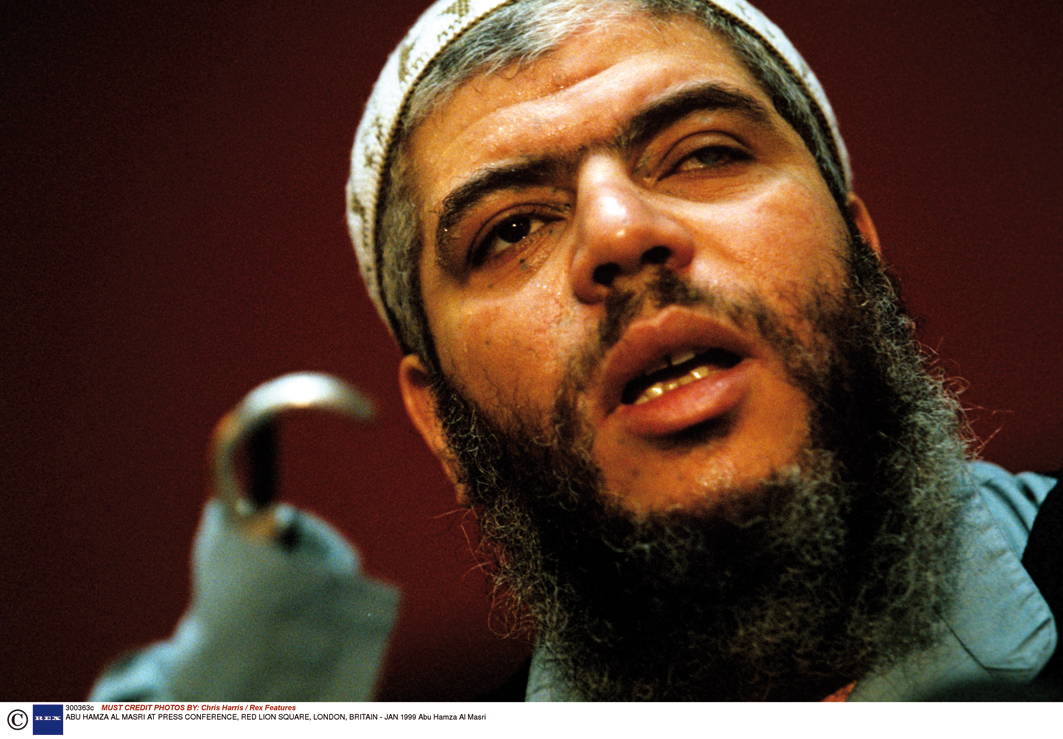

In the second part of his article on the attempt by Abu Hamza to avoid extradition, Paul Hynes QC considers the arguments in the European Court and their compatibility with European notions of cruel and inhuman treatment

In the second part of his article on the attempt by Abu Hamza to avoid extradition, Paul Hynes QC considers the arguments in the European Court and their compatibility with European notions of cruel and inhuman treatment

As we saw in the first part of this article, four men, Babar Ahmad, Haroon Rashid Aswat, Syed Tahla Ahsan and Abu Hamza, exhausted their UK domestic challenges to US extradition, and had to look to Europe for a remedy.

All lodged applications and were successful in obtaining indications, pursuant to r.39 of the Rules of Court, that they should not be extradited until the determination of their complaints. Observations were submitted and the European Court of Human Rights gave a partial decision on the admissibility of the applications on 6 July 2010.

All challenged extradition on the basis of various breaches of their rights under the European Convention on Human Rights (the Convention), namely Arts.2 (right to life); 3 (no torture, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment); 5 (no deprivation of liberty save in accordance with law); 6 (fair trial); 8 (right to private and family life); and 14 (no discrimination).

It was said that the diplomatic assurances were not sufficient to remove the risk of being designated as enemy combatants at the conclusion of the criminal proceedings (Arts.3, 5, 6, and 8); the diplomatic assurances were not sufficient to prevent extraordinary rendition (Arts.3, 5, 6 and 8); there was a real risk that special administrative measures would be applied (Arts.3, 6, 8 and 14); there was a real risk of detention in a “Supermax” prison (Arts.3, 6, 8 and 14); there was a real risk of sentences of life imprisonment without parole and/or extremely long sentences of determinate length (Arts.3 and 8); and, there was a real risk of the use of evidence obtained by inhuman and degrading treatment of third parties contrary to Art.3, resulting in a flagrant denial of justice (Art.6).

In addition, Abu Hamza contended that his designation by the US as an international terrorist would prejudice the jury at any trial (Art.6); and, that extradition to the US would amount to a disproportionate interference with private and family life (Art.8).

Ahmad and Aswat argued that designation as an enemy combatant would place them at real risk of being subjected to capital punishment (Arts.2 and 3); and, detention by the UK authorities pending extradition was not in accordance with law in the absence of a requirement to demonstrate a prima facie case (Art.5).

Ahmad, Aswat and Ahsan submitted that pre-trial publicity would prejudice the jury at any trial, particularly in New York (Art.6); and, the threat of a long sentence would lead to coercive plea bargaining amounting to a flagrant denial of justice (Art.6).

Finally, Ahsan, in a submission adopted by Ahmad and Aswat, asserted the relevance of the fact that the Director of Public Prosecutions had failed properly to consider prosecution in the UK, and that the natural forum for the trial of the allegations was the UK.

The arguments proceeded on the basis that designation would create a real risk of violation of Arts.3, 5 and 6, and so the crux of the matter was the reliability of the US assurances given in the diplomatic notes.

In essence, the conclusion was that the US would be presumed, and could be trusted, to act in good faith, and would honour the assurances. Assurances given in Diplomatic Notes were sufficient for extradition purposes, these were unambiguous and specific to the applicants, a situation not materially altered by the fact that a future US President could not be bound, nor by the lack of an enforcement mechanism available to the applicants personally.

This application was rejected as manifestly ill-founded.

While accepting that extra-judicial transfer of persons for the purposes of detention and interrogation outside the normal legal system where there was a real risk of torture, inhuman or degrading treatment, would be anathema to the rule of law and the values protected by the Convention, the court found no risk of rendition in the applicants’ cases, for reasons similar to those applied in the context of enemy combatant designation.

As far as Abu Hamza was concerned, the theoretical possibility that the US would seek to return him to the UK, but there would be no obligation to receive him in the event that his citizenship had been lawfully revoked, and that he would therefore be removed to Egypt was dismissed as not amounting to a real risk of ill-treatment.

This application was rejected as manifestly ill-founded.

For the same reasons as applied in relation to designation as enemy combatants and extraordinary rendition, the court did not consider that there was a real risk that any applicant would be subjected to the death penalty. This was the case both in respect of the possibility of a superseding capital indictment and trial by a military commission following designation as enemy combatants.

This application was rejected as manifestly ill-founded.

The arguments proceeded on the basis that there was a real risk that the applicants would be subjected to special administrative measures pre-trial, and so the question was whether they would violate Arts.3, 6 and 14.

The court found that, while prolonged solitary confinement amounting to complete sensory and social isolation would breach Art.3, the application of special administrative measures fell short of such treatment, restricting rather than depriving inmates of social contact.

That, along with the readily understandable objectives behind extraordinary security measures and the lack of arbitrariness consequent upon the reasoned decision by the Attorney General to impose them, annual review and judicial challenge, was sufficient to preclude an Art.3 violation, adverse effects of themselves not being sufficient.

An extension of the principles to Art.6, namely that the conditions would coerce a plea bargain, that attorney-client privilege would be undermined or destroyed thereby rendering proper preparation impossible, and that a deterioration in mental health would adversely affect the ability to prepare for and participate in any trial was similarly rejected. The court found that the attorney-client privilege would subsist, such that any necessary instructions could be provided and any complaints and difficulties raised with the court of trial.

It was not considered that a discrete Art.14 issue arose in that there was nothing to suggest that special administrative measures were applied differently to Muslims or to those accused of terrorist offences.

This application was rejected as manifestly ill-founded.

ADX Florence is the only Federal “Supermax” prison facility in the US. All the applicants argued that the conditions there violated art.3 for a variety of reasons.

The UK argued that apart from Abu Hamza, the applicants had failed to exhaust domestic remedies in relation to post-trial detention, raising the point only before the European Court. This contention was rejected on the basis that the relevant information had only come to light during Abu Hamza’s domestic challenge to his extradition, and that the complaint had little prospect of success in light of the High Court’s conclusions as to the engagement of Art.3 on the basis of conditions at ADX Florence in any event.

In Abu Hamza’s case, the court was concerned to analyze whether he was at real risk of detention there. He claimed that he was citing the detention of Omar Abdul Rahman and his own designation as a global terrorist. Acknowledging the possibility, the court concluded that there was no reason to doubt that a timely medical examination would take place, and distinguished Abu Hamza’s position, the gravamen of the Art.3 claim being the prolonged periods of isolation rather than the physical conditions of detention, on the basis that if the conditions were incompatible with his physical disabilities, then he would be moved to a more suitable location.

As to the other applicants, the conclusion was that there was a risk of indefinite detention, without review by an independent judicial authority of the merits and necessity thereof, at ADX Florence, and their complaints raised serious questions of such complexity that any determination must depend on an examination of the merits. Similar considerations applied to the question of post-conviction special administrative measures insofar as the conditions of detention would thereby be made stricter.

Abu Hamza’s application was rejected as manifestly ill-founded, the other applications were declared admissible in relation to Art.3, but manifestly ill founded as far as Arts.6 and 8 are concerned.

The UK argued that apart from Abu Hamza, the applicants had failed to exhaust domestic remedies in relation to the length of detention complaint. This was rejected by the court for reasons similar to those relating to post-trial detention.

Concluding that Ahmad, Aswat and Abu Hamza were at risk of life sentences if convicted, the court was of the view that the complaints raised serious questions of such complexity that their determination should depend on an examination of the merits, and declared the applications admissible.

A similar conclusion was reached in the case of Ahsan as, although his maximum sentence was only 50 years’ imprisonment, his age and the limited scope for reduction were such that he would be nearly 78 years of age before he became eligible for release.

Acknowledging that the question of whether the use of evidence obtained by inhuman or degrading treatment automatically rendered a trial unfair remained open, the court concluded that none of the applicants had demonstrated the real risk of a flagrant denial of justice in the US such as to engage Art.6.

There was no reason to doubt the assurances of the US that the applicants would be tried in a federal court with the full panoply of rights thereby entailed, and even if questions of admissibility did arise, these were capable of being addressed within the trial process and thereafter on appeal. Although various US Courts of Appeal had taken slightly different approaches to the exclusion of coerced evidence, none of them had applied a standard falling sufficiently short of that required in a fair trial to amount to a flagrant denial of justice.

Moreover, while there was little to support the conclusion that evidence obtained indirectly through torture would be adduced in any trial of Abu Hamza, should such evidence arise, its admissibility would be for the trial judge, and subsequently the appropriate appellate court, to determine

This application was rejected as manifestly ill-founded.

The court considered that the suggestion of prejudice arising from pre-trial publicity was without foundation. No Applicant faced allegations connected with the events in New York on 11 September 2001, and clear safeguards are in place in US federal criminal procedure to ensure that jurors are able to try cases impartially.

Finding that the US lacked the necessary discretion and circumspection required in announcing that Abu Hamza was designated under the terms of an order blocking property and prohibiting transactions with persons who commit, threaten to commit or support terrorism, the court nonetheless found that some comment on a matter of such public interest was inevitable, that the charges were distinct from the order, that the burden of proof would remain with the prosecution and that the jury would be directed to try the case on the evidence.

Accepting that plea bargaining was more common and developed in the US than in the UK or other contracting states, the court concluded that European criminal justice systems nonetheless commonly applied a reduction in sentence for a guilty plea and cooperation as appropriate, and saw nothing unlawful or improper in the US practice such as to engage Art.6. That would require a discrepancy between sentences after a trial and on a guilty plea such as to amount to improper pressure, vitiating the right against self incrimination or otherwise providing the only possible way of avoiding a sentence so severe that Art.3 was engaged. Additionally the court relied on the function of the sentencing judge to ensure that the agreement was entered into freely and voluntarily.

The court was similarly unimpressed by the submissions made on behalf of Abu Hamza to the effect that the extradition was tainted by delay and political motivation. Holding that delay was insufficient, the court adopted the conclusions of the High Court as to missing evidence, namely that nothing helpful had been lost, and in any event took the view that any such prejudice could be canvassed before the court of trial.

Concluding that it would only be in exceptional circumstances that private or family life would outweigh the legitimate aim pursued by extradition, Abu Hamza’s additional claim that his extradition was disproportionate was rejected as being not so exceptional, particularly in light of the gravity of the charges.

As far as the appropriate forum for trial was concerned, in the absence of any right not to be extradited or prosecuted in any jurisdiction, the court took the view that it was not competent to determine the more or most appropriate forum for trial, merely to adjudicate upon whether any extradition sought was compatible with the applicant’s rights under the Convention. While the issue might be relevant in the overall assessment of Art.3 in that it went to the search for the requisite fair balance of interest and to the proportionality of the contested extradition decision in a particular case, the findings that Arts.3 and 6 were not engaged in relation to designation, rendition, death penalty, pre-trial detention, pre-trial publicity and plea bargains meant that no question of proportionality arose and the forum was therefore irrelevant.

However, in light of the admissibility of the ADX Florence and general length of detention complaints, the court would not preclude applicants from relying further on the question of forum on the basis that prosecution (and consequently the passing of sentence in the UK), might constitute a more proportionate interference with the applicants’ rights under Arts.3 and 6.

As to the requirement for a prima facie case, the court declined to alter its previous interpretation of Art.5 as requiring only that action is being taken with a view to deportation in order to justify detention.

The admissibility judgement joins issue between Europe and the US. Clear though it is that the US can be trusted to keep its promises, such promises are necessary only because action which it would otherwise take is seemingly in violation of rights under the Convention. Whilst designation as an enemy combatant, trial in military tribunals, the availability of the death penalty and the use of rendition were all thought to create a real risk of Convention violations, and therefore to require assurances that they would not occur, it remains to be seen whether the length of sentence on conviction, conditions in “Supermax” prisons and special administrative measures are in fact compatible with European notions of cruel and inhuman treatment, notwithstanding that they constitute settled US penal policy and practice.

Paul Hynes QC is a criminal defence specialist, 25 Bedford Row.

All lodged applications and were successful in obtaining indications, pursuant to r.39 of the Rules of Court, that they should not be extradited until the determination of their complaints. Observations were submitted and the European Court of Human Rights gave a partial decision on the admissibility of the applications on 6 July 2010.

All challenged extradition on the basis of various breaches of their rights under the European Convention on Human Rights (the Convention), namely Arts.2 (right to life); 3 (no torture, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment); 5 (no deprivation of liberty save in accordance with law); 6 (fair trial); 8 (right to private and family life); and 14 (no discrimination).

It was said that the diplomatic assurances were not sufficient to remove the risk of being designated as enemy combatants at the conclusion of the criminal proceedings (Arts.3, 5, 6, and 8); the diplomatic assurances were not sufficient to prevent extraordinary rendition (Arts.3, 5, 6 and 8); there was a real risk that special administrative measures would be applied (Arts.3, 6, 8 and 14); there was a real risk of detention in a “Supermax” prison (Arts.3, 6, 8 and 14); there was a real risk of sentences of life imprisonment without parole and/or extremely long sentences of determinate length (Arts.3 and 8); and, there was a real risk of the use of evidence obtained by inhuman and degrading treatment of third parties contrary to Art.3, resulting in a flagrant denial of justice (Art.6).

In addition, Abu Hamza contended that his designation by the US as an international terrorist would prejudice the jury at any trial (Art.6); and, that extradition to the US would amount to a disproportionate interference with private and family life (Art.8).

Ahmad and Aswat argued that designation as an enemy combatant would place them at real risk of being subjected to capital punishment (Arts.2 and 3); and, detention by the UK authorities pending extradition was not in accordance with law in the absence of a requirement to demonstrate a prima facie case (Art.5).

Ahmad, Aswat and Ahsan submitted that pre-trial publicity would prejudice the jury at any trial, particularly in New York (Art.6); and, the threat of a long sentence would lead to coercive plea bargaining amounting to a flagrant denial of justice (Art.6).

Finally, Ahsan, in a submission adopted by Ahmad and Aswat, asserted the relevance of the fact that the Director of Public Prosecutions had failed properly to consider prosecution in the UK, and that the natural forum for the trial of the allegations was the UK.

The arguments proceeded on the basis that designation would create a real risk of violation of Arts.3, 5 and 6, and so the crux of the matter was the reliability of the US assurances given in the diplomatic notes.

In essence, the conclusion was that the US would be presumed, and could be trusted, to act in good faith, and would honour the assurances. Assurances given in Diplomatic Notes were sufficient for extradition purposes, these were unambiguous and specific to the applicants, a situation not materially altered by the fact that a future US President could not be bound, nor by the lack of an enforcement mechanism available to the applicants personally.

This application was rejected as manifestly ill-founded.

While accepting that extra-judicial transfer of persons for the purposes of detention and interrogation outside the normal legal system where there was a real risk of torture, inhuman or degrading treatment, would be anathema to the rule of law and the values protected by the Convention, the court found no risk of rendition in the applicants’ cases, for reasons similar to those applied in the context of enemy combatant designation.

As far as Abu Hamza was concerned, the theoretical possibility that the US would seek to return him to the UK, but there would be no obligation to receive him in the event that his citizenship had been lawfully revoked, and that he would therefore be removed to Egypt was dismissed as not amounting to a real risk of ill-treatment.

This application was rejected as manifestly ill-founded.

For the same reasons as applied in relation to designation as enemy combatants and extraordinary rendition, the court did not consider that there was a real risk that any applicant would be subjected to the death penalty. This was the case both in respect of the possibility of a superseding capital indictment and trial by a military commission following designation as enemy combatants.

This application was rejected as manifestly ill-founded.

The arguments proceeded on the basis that there was a real risk that the applicants would be subjected to special administrative measures pre-trial, and so the question was whether they would violate Arts.3, 6 and 14.

The court found that, while prolonged solitary confinement amounting to complete sensory and social isolation would breach Art.3, the application of special administrative measures fell short of such treatment, restricting rather than depriving inmates of social contact.

That, along with the readily understandable objectives behind extraordinary security measures and the lack of arbitrariness consequent upon the reasoned decision by the Attorney General to impose them, annual review and judicial challenge, was sufficient to preclude an Art.3 violation, adverse effects of themselves not being sufficient.

An extension of the principles to Art.6, namely that the conditions would coerce a plea bargain, that attorney-client privilege would be undermined or destroyed thereby rendering proper preparation impossible, and that a deterioration in mental health would adversely affect the ability to prepare for and participate in any trial was similarly rejected. The court found that the attorney-client privilege would subsist, such that any necessary instructions could be provided and any complaints and difficulties raised with the court of trial.

It was not considered that a discrete Art.14 issue arose in that there was nothing to suggest that special administrative measures were applied differently to Muslims or to those accused of terrorist offences.

This application was rejected as manifestly ill-founded.

ADX Florence is the only Federal “Supermax” prison facility in the US. All the applicants argued that the conditions there violated art.3 for a variety of reasons.

The UK argued that apart from Abu Hamza, the applicants had failed to exhaust domestic remedies in relation to post-trial detention, raising the point only before the European Court. This contention was rejected on the basis that the relevant information had only come to light during Abu Hamza’s domestic challenge to his extradition, and that the complaint had little prospect of success in light of the High Court’s conclusions as to the engagement of Art.3 on the basis of conditions at ADX Florence in any event.

In Abu Hamza’s case, the court was concerned to analyze whether he was at real risk of detention there. He claimed that he was citing the detention of Omar Abdul Rahman and his own designation as a global terrorist. Acknowledging the possibility, the court concluded that there was no reason to doubt that a timely medical examination would take place, and distinguished Abu Hamza’s position, the gravamen of the Art.3 claim being the prolonged periods of isolation rather than the physical conditions of detention, on the basis that if the conditions were incompatible with his physical disabilities, then he would be moved to a more suitable location.

As to the other applicants, the conclusion was that there was a risk of indefinite detention, without review by an independent judicial authority of the merits and necessity thereof, at ADX Florence, and their complaints raised serious questions of such complexity that any determination must depend on an examination of the merits. Similar considerations applied to the question of post-conviction special administrative measures insofar as the conditions of detention would thereby be made stricter.

Abu Hamza’s application was rejected as manifestly ill-founded, the other applications were declared admissible in relation to Art.3, but manifestly ill founded as far as Arts.6 and 8 are concerned.

The UK argued that apart from Abu Hamza, the applicants had failed to exhaust domestic remedies in relation to the length of detention complaint. This was rejected by the court for reasons similar to those relating to post-trial detention.

Concluding that Ahmad, Aswat and Abu Hamza were at risk of life sentences if convicted, the court was of the view that the complaints raised serious questions of such complexity that their determination should depend on an examination of the merits, and declared the applications admissible.

A similar conclusion was reached in the case of Ahsan as, although his maximum sentence was only 50 years’ imprisonment, his age and the limited scope for reduction were such that he would be nearly 78 years of age before he became eligible for release.

Acknowledging that the question of whether the use of evidence obtained by inhuman or degrading treatment automatically rendered a trial unfair remained open, the court concluded that none of the applicants had demonstrated the real risk of a flagrant denial of justice in the US such as to engage Art.6.

There was no reason to doubt the assurances of the US that the applicants would be tried in a federal court with the full panoply of rights thereby entailed, and even if questions of admissibility did arise, these were capable of being addressed within the trial process and thereafter on appeal. Although various US Courts of Appeal had taken slightly different approaches to the exclusion of coerced evidence, none of them had applied a standard falling sufficiently short of that required in a fair trial to amount to a flagrant denial of justice.

Moreover, while there was little to support the conclusion that evidence obtained indirectly through torture would be adduced in any trial of Abu Hamza, should such evidence arise, its admissibility would be for the trial judge, and subsequently the appropriate appellate court, to determine

This application was rejected as manifestly ill-founded.

The court considered that the suggestion of prejudice arising from pre-trial publicity was without foundation. No Applicant faced allegations connected with the events in New York on 11 September 2001, and clear safeguards are in place in US federal criminal procedure to ensure that jurors are able to try cases impartially.

Finding that the US lacked the necessary discretion and circumspection required in announcing that Abu Hamza was designated under the terms of an order blocking property and prohibiting transactions with persons who commit, threaten to commit or support terrorism, the court nonetheless found that some comment on a matter of such public interest was inevitable, that the charges were distinct from the order, that the burden of proof would remain with the prosecution and that the jury would be directed to try the case on the evidence.

Accepting that plea bargaining was more common and developed in the US than in the UK or other contracting states, the court concluded that European criminal justice systems nonetheless commonly applied a reduction in sentence for a guilty plea and cooperation as appropriate, and saw nothing unlawful or improper in the US practice such as to engage Art.6. That would require a discrepancy between sentences after a trial and on a guilty plea such as to amount to improper pressure, vitiating the right against self incrimination or otherwise providing the only possible way of avoiding a sentence so severe that Art.3 was engaged. Additionally the court relied on the function of the sentencing judge to ensure that the agreement was entered into freely and voluntarily.

The court was similarly unimpressed by the submissions made on behalf of Abu Hamza to the effect that the extradition was tainted by delay and political motivation. Holding that delay was insufficient, the court adopted the conclusions of the High Court as to missing evidence, namely that nothing helpful had been lost, and in any event took the view that any such prejudice could be canvassed before the court of trial.

Concluding that it would only be in exceptional circumstances that private or family life would outweigh the legitimate aim pursued by extradition, Abu Hamza’s additional claim that his extradition was disproportionate was rejected as being not so exceptional, particularly in light of the gravity of the charges.

As far as the appropriate forum for trial was concerned, in the absence of any right not to be extradited or prosecuted in any jurisdiction, the court took the view that it was not competent to determine the more or most appropriate forum for trial, merely to adjudicate upon whether any extradition sought was compatible with the applicant’s rights under the Convention. While the issue might be relevant in the overall assessment of Art.3 in that it went to the search for the requisite fair balance of interest and to the proportionality of the contested extradition decision in a particular case, the findings that Arts.3 and 6 were not engaged in relation to designation, rendition, death penalty, pre-trial detention, pre-trial publicity and plea bargains meant that no question of proportionality arose and the forum was therefore irrelevant.

However, in light of the admissibility of the ADX Florence and general length of detention complaints, the court would not preclude applicants from relying further on the question of forum on the basis that prosecution (and consequently the passing of sentence in the UK), might constitute a more proportionate interference with the applicants’ rights under Arts.3 and 6.

As to the requirement for a prima facie case, the court declined to alter its previous interpretation of Art.5 as requiring only that action is being taken with a view to deportation in order to justify detention.

The admissibility judgement joins issue between Europe and the US. Clear though it is that the US can be trusted to keep its promises, such promises are necessary only because action which it would otherwise take is seemingly in violation of rights under the Convention. Whilst designation as an enemy combatant, trial in military tribunals, the availability of the death penalty and the use of rendition were all thought to create a real risk of Convention violations, and therefore to require assurances that they would not occur, it remains to be seen whether the length of sentence on conviction, conditions in “Supermax” prisons and special administrative measures are in fact compatible with European notions of cruel and inhuman treatment, notwithstanding that they constitute settled US penal policy and practice.

Paul Hynes QC is a criminal defence specialist, 25 Bedford Row.

In the second part of his article on the attempt by Abu Hamza to avoid extradition, Paul Hynes QC considers the arguments in the European Court and their compatibility with European notions of cruel and inhuman treatment

In the second part of his article on the attempt by Abu Hamza to avoid extradition, Paul Hynes QC considers the arguments in the European Court and their compatibility with European notions of cruel and inhuman treatment

As we saw in the first part of this article, four men, Babar Ahmad, Haroon Rashid Aswat, Syed Tahla Ahsan and Abu Hamza, exhausted their UK domestic challenges to US extradition, and had to look to Europe for a remedy.

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar