*/

In the first of two articles, Paul Hynes QC examines the events leading to the extradition of Abu Hamza reaching the European Court

In the first of two articles, Paul Hynes QC examines the events leading to the extradition of Abu Hamza reaching the European Court

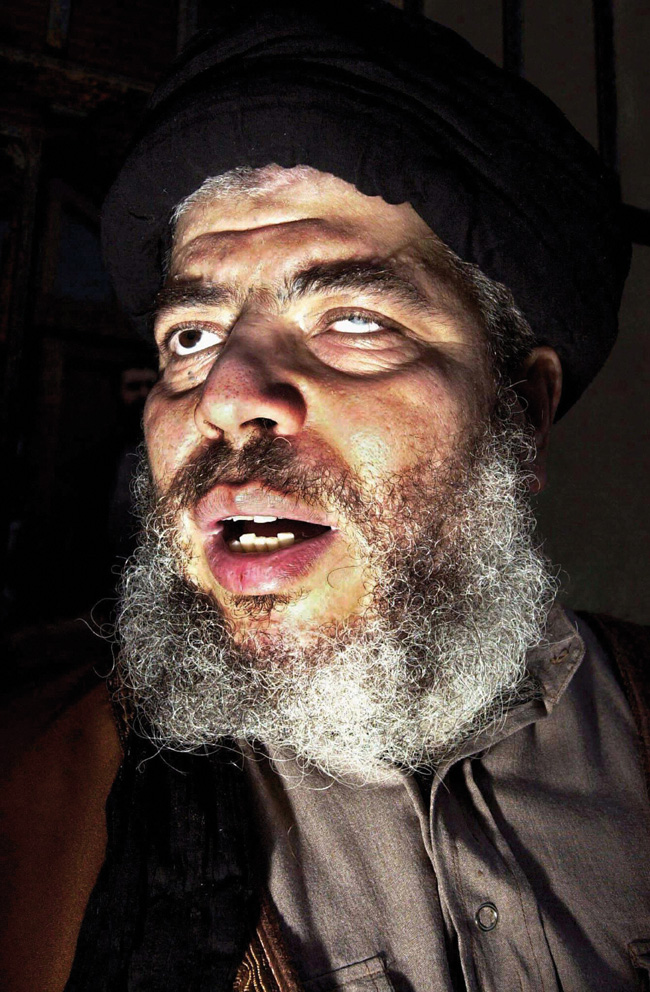

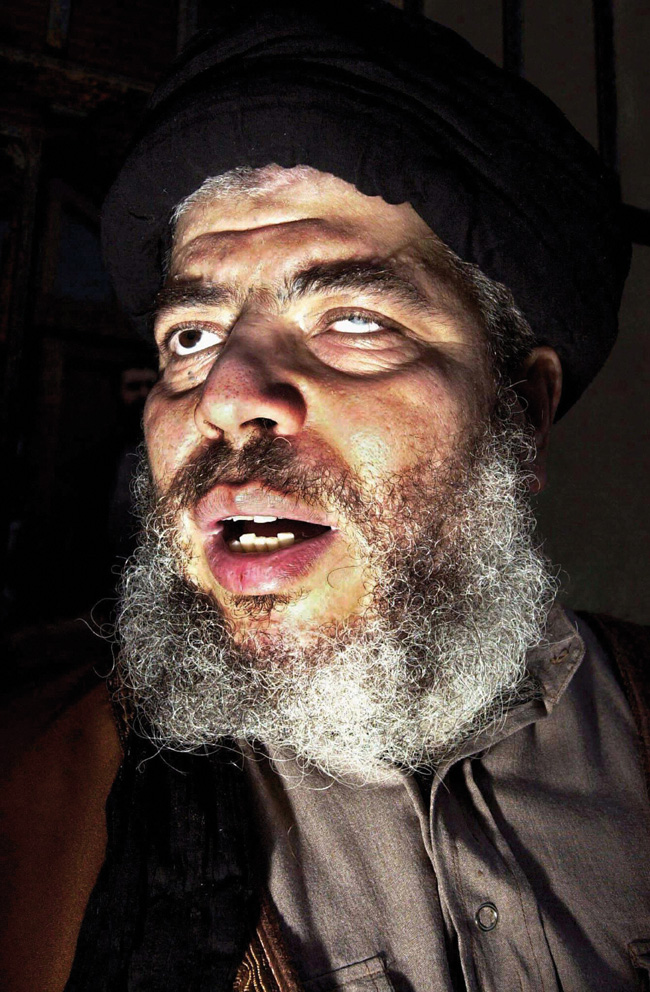

It is ironic that the decision on whether Abu Hamza remains in the UK or stands trial in the US is to be made in Europe. Although the British first arrested him in 1999, it wasn’t until 2003 that the UK authorities raided Finsbury Park Mosque and the Home Secretary served notice of his intention to deprive Abu Hamza of his British citizenship.

Those proceedings were finally determined in his favour in November, but in the meantime a criminal trial and a US extradition request had occupied the UK courts. Although the latter started first, with Abu Hamza’s arrest in May 2004, it remains the last unresolved question of legal substance, and now the sole reason behind his detention.

There are two sets of allegations outstanding against four men, Babar Ahmad, Haroon Rashid Aswat, Syed Tahla Ahsan and Abu Hamza. These separate proceedings have been joined as they raise similar legal and factual issues in connection with US extradition requests.

First, Ahmad and Ahsan are facing charges of conspiracy to provide material support to terrorists; providing material support to terrorists; conspiracy to kill, kidnap, main or injure persons or damage property in a foreign country; and, in relation to Babar Ahmad only, money laundering, between 1997 and 2004 in Connecticut. The charges are based on involvement in the operation of a web site, the servers of which were based in Connecticut, and the possession of a classified US naval document relating to battle fleet operations and potential vulnerabilities in the Straits of Hormuz.

Second, Abu Hamza faces indictments in New York alleging complicity in the kidnapping of 16 hostages in Yemen in 1998, the conduct of violent jihad by the Taliban in Afghanistan in 2001, and the establishment of a jihad training camp in Oregon in 2000/01. It is in respect of the Oregon matters that Haroon Rashid (and Oussama Abdullah Kassir) are said to be co-conspirators.

These charges rely on contact with the leader of the kidnappers, Abu Ali-Hassan, who was subsequently tried, convicted and executed; the provision of material and financial assistance to individuals who wished to join the Taliban and facilitating contact with Taliban leaders, the provision of material support and resources, and conspiring to supply goods and services, to the Taliban in Afghanistan; and, providing material support and resources to Al Qaeda in the form of the Oregon training camp.

The Yemen charges against Abu Hamza are based on the purchase of a satellite telephone and the nature and timing of his contact with the kidnappers. Evidentially, the position with regard to the Afghanistan and Oregon matters is more complicated.

A principal prosecution witness (and alleged co-conspirator) in relation to both is James Ujaama, a US citizen. Abu Hamza is said to have facilitated contact between the Taliban, Ujaama and another man (also said to be a co-conspirator) Feroz Abassi, with a view to those two individuals participating in violent jihad. Abassi was detained in Afghanistan and eventually returned to the UK via the US detention facility at Guantánamo Bay.

Ujaama was charged in the US and entered into a plea bargain, in which the US agreed not to detain him as an “enemy combatant”, and lifted the “special administrative measures” to which he had hitherto been subjected, as a result of which a sentence of two years’ imprisonment was imposed, consequent upon him becoming a prosecution witness. Ujaama subsequently gave evidence against Oussama Kassir, who had been extradited from the Czech Republic and, following his conviction in relation to a number of charges relating to the Oregon training camp in 2009, was sentenced to life imprisonment on each count.

A further alleged co-conspirator in relation to the Afghanistan allegations, Ibn Al-Shaykh Al-Libi, was also arrested there and then transferred to Guantánamo Bay. It was suggested that he had been subjected to extraordinary rendition to Libya and Egypt, possibly later sentenced to life imprisonment in Libya and thereafter, according to Libyan media reports, committed suicide while in prison.

Although Abu Hamza was the subject of the first extradition request, the intervention of his domestic proceedings in August 2004 meant that Ahmed’s case was the first to be substantively considered in the magistrates’ court.

The US relied on Diplomatic Note No.25, which assured the UK that the death penalty would not be sought or imposed. It also stated that any prosecution would take place before a Federal Court in accordance with the full panoply of rights and protections that would otherwise be afforded to a defendant facing similar charges; that there would be no prosecution before a military commission as specified in the President’s Military Order of the November 13, 2001; and, that Ahmed would not be designated as an enemy combatant.

The effectiveness of these assurances were at the forefront of the submissions made on Ahmad’s behalf to the effect that: the death penalty could still be imposed on a superseding indictment; that he remained at risk of “enemy combatant” designation pursuant to US Military Order No.1; that he remained at risk of extraordinary rendition; and that there was a substantial risk of “special administrative measures” being applied in breach of Arts 3 and 6 of the Convention.

Although Senior District Judge Workman described the case as “difficult and troubling”, he was satisfied that the assurances would be kept and that the application of special administrative measures would not violate Ahmad’s Art.6 rights. The case was committed to the Secretary of State for a decision as to extradition and, when extradition was ordered, was appealed to the High Court.

Meanwhile, Haroon Aswat had been arrested pursuant to a US extradition request. His case took a similar course to that of Ahmad, save that it was submitted additionally on his behalf that reliance upon the testimony of Ujaama would violate his Art 6 rights. The Judge was unconvinced, ruling that admissibility of evidence was a matter for the court of trial. The case was committed to the Secretary of State for a decision as to extradition and, when extradition was ordered, was appealed to the High Court.

The appeals of Ahmad and Aswat were heard together and rejected on November 30, 2006. The Court of Appeal held that it was not inevitable that evidence obtained as a result of torture or inhuman and degrading treatment would be used against them in any US trial, that in any event evidence obtained by torture would be excluded, and that obtained by other forms of ill-treatment recognized as having little if any probative value. Even if Ujaama had been coerced by special administrative measures and/or the threat of indefinite detention, this fell short of establishing that he had been subjected to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.

The Diplomatic Notes could be relied upon, unlike other cases where, although there had been designation, it had occurred in the absence of undertakings. The application of special administrative measures did not constitute inhuman or degrading treatment, did not violate Art 6 and were not applied in a way which discriminated on the grounds of race or religion. Permission to appeal to the House of Lords was refused in June 2007 [Ahmad and Aswat v US [2006] EWHC 2927 (Admin)].

The US applied for the extradition of Ahsan in September 2006. That case followed the now familiar route, resulting in committal to the Secretary of State for a decision on extradition and, when ordered, was appealed to the High Court. The appeal was dismissed in April 2008 and permission to appeal to the House of Lords was refused in May [Ahsan v US [2008] EWHC 666 (Admin)].

Abu Hamza’s extradition, somewhat delayed by his domestic criminal trial, found itself at the back of the queue. In October 2007 it was argued that further disclosure concerning the circumstances in which evidence came into the hands of the US should be provided. Although further information was forthcoming, the substance of the submission was rejected on the basis that the Yemen allegations did not rely on any material founded upon or obtained by torture; that all references to information obtained from Abassi had been removed from the extradition request and that, insofar as Ibn Al-Libi was concerned, he was a co-conspirator and nothing in the extradition request could plausibly be considered to have been obtained from him directly or indirectly through torture.

At the full extradition hearing, arguments deployed on behalf of Abu Hamza to the effect that it should not proceed on the basis of delay and the consequent loss of evidence; that it would constitute a disproportionate interference with his family and private life contrary to Art 8; and, that his probable detention in a “Supermax” prison facility and/or the imposition of special administrative measures and/or the real risk of re-extradition or rendition to a third country would violate his rights pursuant to Art 3 were all rejected. The case was committed to the Secretary of State for a decision as to extradition and, when extradition was ordered, the matter was appealed to the High Court.

The appeal was dismissed in June 2008. It was concluded that Ujaama’s plea bargain could not remotely be considered torture or ill-treatment; that Abassi’s evidence was not relied upon and would in any event constitute inadmissible hearsay, and that Ibn Al-Libi was a co-conspirator and not a witness. Finding nothing in the submission that the extradition request or any evidence at trial would be based indirectly on torture, and that in any event there was no material difference in the admissibility of such material in the US, the court turned to the assurances. The analysis was robust: “… if we need to look for a guarantee that the US will honour its diplomatic assurances, the history of unswerving compliance with them provides a sure guide. We are satisfied that these diplomatic assurances will be honoured.”

As to the length and conditions of any sentence, it was found that a whole-life tariff would not of itself constitute a breach of Art 3, and that the conditions in a “Supermax” prison would be assessed against Abu Hamza’s medical evaluation such that, if incompatible with his ability to cope, he could expect to be moved to a more suitable medical centre.

Finally, accepting that the US was the appropriate forum for any trial, and that the proceedings had not been viable until 2003, the court concluded that there was nothing of assistance which had been lost by the delay. Abu Hamza’s appeal was dismissed and permission to appeal to the House of Lords was refused in July 2008, Mustafa v US [2008] EWHC 1357 (Admin). With that, the domestic challenge was at an end, and Abu Hamza needed to seek his remedy in Europe with others raising similar issues.

In Part Two, published next month, Paul Hynes QC considers the arguments in the European Court and their compatibility with European notions of cruel and inhuman treatment.

Paul Hynes QC is a criminal defence specialist, 25 Bedford Row.

Those proceedings were finally determined in his favour in November, but in the meantime a criminal trial and a US extradition request had occupied the UK courts. Although the latter started first, with Abu Hamza’s arrest in May 2004, it remains the last unresolved question of legal substance, and now the sole reason behind his detention.

There are two sets of allegations outstanding against four men, Babar Ahmad, Haroon Rashid Aswat, Syed Tahla Ahsan and Abu Hamza. These separate proceedings have been joined as they raise similar legal and factual issues in connection with US extradition requests.

First, Ahmad and Ahsan are facing charges of conspiracy to provide material support to terrorists; providing material support to terrorists; conspiracy to kill, kidnap, main or injure persons or damage property in a foreign country; and, in relation to Babar Ahmad only, money laundering, between 1997 and 2004 in Connecticut. The charges are based on involvement in the operation of a web site, the servers of which were based in Connecticut, and the possession of a classified US naval document relating to battle fleet operations and potential vulnerabilities in the Straits of Hormuz.

Second, Abu Hamza faces indictments in New York alleging complicity in the kidnapping of 16 hostages in Yemen in 1998, the conduct of violent jihad by the Taliban in Afghanistan in 2001, and the establishment of a jihad training camp in Oregon in 2000/01. It is in respect of the Oregon matters that Haroon Rashid (and Oussama Abdullah Kassir) are said to be co-conspirators.

These charges rely on contact with the leader of the kidnappers, Abu Ali-Hassan, who was subsequently tried, convicted and executed; the provision of material and financial assistance to individuals who wished to join the Taliban and facilitating contact with Taliban leaders, the provision of material support and resources, and conspiring to supply goods and services, to the Taliban in Afghanistan; and, providing material support and resources to Al Qaeda in the form of the Oregon training camp.

The Yemen charges against Abu Hamza are based on the purchase of a satellite telephone and the nature and timing of his contact with the kidnappers. Evidentially, the position with regard to the Afghanistan and Oregon matters is more complicated.

A principal prosecution witness (and alleged co-conspirator) in relation to both is James Ujaama, a US citizen. Abu Hamza is said to have facilitated contact between the Taliban, Ujaama and another man (also said to be a co-conspirator) Feroz Abassi, with a view to those two individuals participating in violent jihad. Abassi was detained in Afghanistan and eventually returned to the UK via the US detention facility at Guantánamo Bay.

Ujaama was charged in the US and entered into a plea bargain, in which the US agreed not to detain him as an “enemy combatant”, and lifted the “special administrative measures” to which he had hitherto been subjected, as a result of which a sentence of two years’ imprisonment was imposed, consequent upon him becoming a prosecution witness. Ujaama subsequently gave evidence against Oussama Kassir, who had been extradited from the Czech Republic and, following his conviction in relation to a number of charges relating to the Oregon training camp in 2009, was sentenced to life imprisonment on each count.

A further alleged co-conspirator in relation to the Afghanistan allegations, Ibn Al-Shaykh Al-Libi, was also arrested there and then transferred to Guantánamo Bay. It was suggested that he had been subjected to extraordinary rendition to Libya and Egypt, possibly later sentenced to life imprisonment in Libya and thereafter, according to Libyan media reports, committed suicide while in prison.

Although Abu Hamza was the subject of the first extradition request, the intervention of his domestic proceedings in August 2004 meant that Ahmed’s case was the first to be substantively considered in the magistrates’ court.

The US relied on Diplomatic Note No.25, which assured the UK that the death penalty would not be sought or imposed. It also stated that any prosecution would take place before a Federal Court in accordance with the full panoply of rights and protections that would otherwise be afforded to a defendant facing similar charges; that there would be no prosecution before a military commission as specified in the President’s Military Order of the November 13, 2001; and, that Ahmed would not be designated as an enemy combatant.

The effectiveness of these assurances were at the forefront of the submissions made on Ahmad’s behalf to the effect that: the death penalty could still be imposed on a superseding indictment; that he remained at risk of “enemy combatant” designation pursuant to US Military Order No.1; that he remained at risk of extraordinary rendition; and that there was a substantial risk of “special administrative measures” being applied in breach of Arts 3 and 6 of the Convention.

Although Senior District Judge Workman described the case as “difficult and troubling”, he was satisfied that the assurances would be kept and that the application of special administrative measures would not violate Ahmad’s Art.6 rights. The case was committed to the Secretary of State for a decision as to extradition and, when extradition was ordered, was appealed to the High Court.

Meanwhile, Haroon Aswat had been arrested pursuant to a US extradition request. His case took a similar course to that of Ahmad, save that it was submitted additionally on his behalf that reliance upon the testimony of Ujaama would violate his Art 6 rights. The Judge was unconvinced, ruling that admissibility of evidence was a matter for the court of trial. The case was committed to the Secretary of State for a decision as to extradition and, when extradition was ordered, was appealed to the High Court.

The appeals of Ahmad and Aswat were heard together and rejected on November 30, 2006. The Court of Appeal held that it was not inevitable that evidence obtained as a result of torture or inhuman and degrading treatment would be used against them in any US trial, that in any event evidence obtained by torture would be excluded, and that obtained by other forms of ill-treatment recognized as having little if any probative value. Even if Ujaama had been coerced by special administrative measures and/or the threat of indefinite detention, this fell short of establishing that he had been subjected to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.

The Diplomatic Notes could be relied upon, unlike other cases where, although there had been designation, it had occurred in the absence of undertakings. The application of special administrative measures did not constitute inhuman or degrading treatment, did not violate Art 6 and were not applied in a way which discriminated on the grounds of race or religion. Permission to appeal to the House of Lords was refused in June 2007 [Ahmad and Aswat v US [2006] EWHC 2927 (Admin)].

The US applied for the extradition of Ahsan in September 2006. That case followed the now familiar route, resulting in committal to the Secretary of State for a decision on extradition and, when ordered, was appealed to the High Court. The appeal was dismissed in April 2008 and permission to appeal to the House of Lords was refused in May [Ahsan v US [2008] EWHC 666 (Admin)].

Abu Hamza’s extradition, somewhat delayed by his domestic criminal trial, found itself at the back of the queue. In October 2007 it was argued that further disclosure concerning the circumstances in which evidence came into the hands of the US should be provided. Although further information was forthcoming, the substance of the submission was rejected on the basis that the Yemen allegations did not rely on any material founded upon or obtained by torture; that all references to information obtained from Abassi had been removed from the extradition request and that, insofar as Ibn Al-Libi was concerned, he was a co-conspirator and nothing in the extradition request could plausibly be considered to have been obtained from him directly or indirectly through torture.

At the full extradition hearing, arguments deployed on behalf of Abu Hamza to the effect that it should not proceed on the basis of delay and the consequent loss of evidence; that it would constitute a disproportionate interference with his family and private life contrary to Art 8; and, that his probable detention in a “Supermax” prison facility and/or the imposition of special administrative measures and/or the real risk of re-extradition or rendition to a third country would violate his rights pursuant to Art 3 were all rejected. The case was committed to the Secretary of State for a decision as to extradition and, when extradition was ordered, the matter was appealed to the High Court.

The appeal was dismissed in June 2008. It was concluded that Ujaama’s plea bargain could not remotely be considered torture or ill-treatment; that Abassi’s evidence was not relied upon and would in any event constitute inadmissible hearsay, and that Ibn Al-Libi was a co-conspirator and not a witness. Finding nothing in the submission that the extradition request or any evidence at trial would be based indirectly on torture, and that in any event there was no material difference in the admissibility of such material in the US, the court turned to the assurances. The analysis was robust: “… if we need to look for a guarantee that the US will honour its diplomatic assurances, the history of unswerving compliance with them provides a sure guide. We are satisfied that these diplomatic assurances will be honoured.”

As to the length and conditions of any sentence, it was found that a whole-life tariff would not of itself constitute a breach of Art 3, and that the conditions in a “Supermax” prison would be assessed against Abu Hamza’s medical evaluation such that, if incompatible with his ability to cope, he could expect to be moved to a more suitable medical centre.

Finally, accepting that the US was the appropriate forum for any trial, and that the proceedings had not been viable until 2003, the court concluded that there was nothing of assistance which had been lost by the delay. Abu Hamza’s appeal was dismissed and permission to appeal to the House of Lords was refused in July 2008, Mustafa v US [2008] EWHC 1357 (Admin). With that, the domestic challenge was at an end, and Abu Hamza needed to seek his remedy in Europe with others raising similar issues.

In Part Two, published next month, Paul Hynes QC considers the arguments in the European Court and their compatibility with European notions of cruel and inhuman treatment.

Paul Hynes QC is a criminal defence specialist, 25 Bedford Row.

In the first of two articles, Paul Hynes QC examines the events leading to the extradition of Abu Hamza reaching the European Court

In the first of two articles, Paul Hynes QC examines the events leading to the extradition of Abu Hamza reaching the European Court

It is ironic that the decision on whether Abu Hamza remains in the UK or stands trial in the US is to be made in Europe. Although the British first arrested him in 1999, it wasn’t until 2003 that the UK authorities raided Finsbury Park Mosque and the Home Secretary served notice of his intention to deprive Abu Hamza of his British citizenship.

Kirsty Brimelow KC, Chair of the Bar, sets our course for 2026

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Asks Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

AlphaBiolabs has donated £500 to The Christie Charity through its Giving Back initiative, helping to support cancer care, treatment and research across Greater Manchester, Cheshire and further afield

Q and A with criminal barrister Nick Murphy, who moved to New Park Court Chambers on the North Eastern Circuit in search of a better work-life balance

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar

Jury-less trial proposals threaten fairness, legitimacy and democracy without ending the backlog, writes Professor Cheryl Thomas KC (Hon), the UK’s leading expert on juries, judges and courts

Are you ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC explains the biggest change since HMRC launched self-assessment more than 30 years ago... and its impact on the Bar

Marking one year since a Bar disciplinary tribunal dismissed all charges against her, Dr Charlotte Proudman discusses the experience, her formative years and next steps. Interview by Anthony Inglese CB