*/

Imposing a professional obligation to act in a way that advances equality, diversity and inclusion is the wrong way to achieve this ambition, says Nick Vineall KC

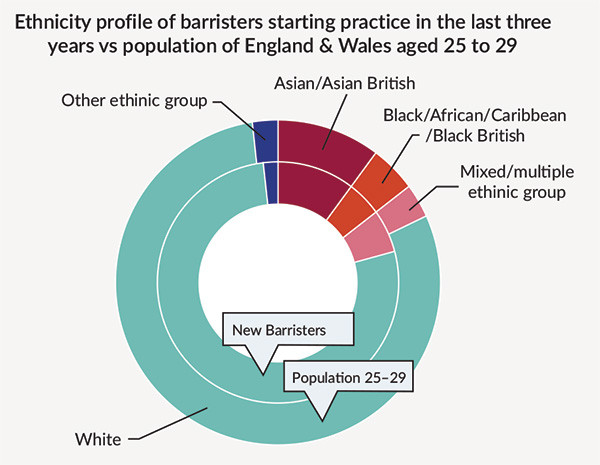

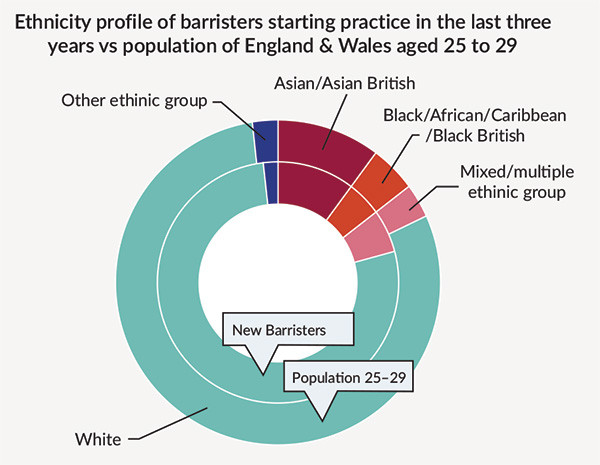

Much has been done by the Bar Council, the Inns, the Circuits, the Legal Practice Management Association and Institute of Barristers’ Clerks, and the Bar Standards Board (BSB), to try to overcome unfairness or discrimination, and to improve diversity at the Bar. The intake to the practising Bar is now broadly reflective of the overall demographic (apart from the fact that women are overrepresented):

© Bar Council

But there remain real challenges with retention and progression. Despite all the efforts of the profession, there are some profoundly disquieting disparities between the earnings of men and women, and white and non-white barristers, even in the early years of practice (so this ongoing, not a historical hangover). Nobody has yet achieved a good analysis of exactly what causes these differences. There are many possible factors which could be at play: unequal prior access to educational opportunities; hours worked; discrimination by clients; unconscious bias in selection processes; people’s pre-existing contacts; and more generally what is sometimes called social or cultural capital. Perhaps there is also some straightforward unlawful discrimination within chambers – though that seems unlikely to be a major factor given the very few established occasions of it happening.

These continuing disparities in the progression of different groups at the Bar has led the BSB to suggest that the Code of Conduct should do more than merely prohibit unlawful discrimination, and should impose on barristers, by way of professional obligation, a positive duty to act in a way that advances equality, diversity and inclusion. This is understandable, and undoubtedly well-intentioned. But it seems to me to be problematic, and I hope the BSB will not proceed with the change.

In our Code of Conduct the ten core duties underpin the entire regulatory framework.

Core Duty 8 says: ‘You must not discriminate unlawfully against any person.’ That restates a legal obligation which applies to us anyway, but it means that regulatory sanctions are readily available for breaching it. It is easy to understand what it means and it is a good duty to have.

The BSB wants to change this to: ‘You must act in a way that advances equality, diversity and inclusion.’ And the BSB also proposes some new Equality Rules to explain what is required.

There is no definition of equality, diversity or inclusion in the present handbook but the BSB’s consultation tells us what it means by these words. Equality means equality of opportunity. Diversity means ‘ensuring that profession is reflective of the population it serves’. Inclusion means ‘creating a respectful environment and culture where people feel valued and are able to participate and reach their full potential’.

The BSB says that compliance with the new Core Duty and Equality Rules ‘is not necessarily to have achieved equality of outcome, but to have taken reasonable steps and to have demonstrated progress over time.’ The BSB’s purpose in making the rule change is ‘to achiev[e] behaviour and cultural change across the profession’.

Making conduct rules is the wrong way to achieve this ambition.

There are practical difficulties because there will inevitably be uncertainty as to what has to be done to satisfy the duty, and how much is enough.

But I think there is a point of principle lurking here too. Is it a proper purpose of a code of conduct to achieve cultural change? Or is the purpose of conduct rules better limited to ensuring that clients are properly served by the professionals in whom they place their trust?

The Code of Conduct is at its heart about maintaining minimum standards for our practice. Those standards ought to be focused on our professional job, which is the privilege of representing our clients without fear or favour, and that is why those minimum standards are set high. The core duties rightly focus on our duties to the court, to our clients, and to the administration of justice.

Is it appropriate for the BSB to impose on barristers a positive duty to promote various features of the profession which are plainly secondary to our core role as barristers, even where what is to be promoted is a desirable social good like equality of opportunity? Is it properly the role of the regulator to compel me, as part of the price of practising, to promote the social goods that the BSB has identified? What if I would prefer to direct that same effort to ensuring my chambers was carbon-neutral? Or to my particular conception of social justice?

It is one thing to legislate or regulate to prevent harm. It is quite another to legislate or regulate to compel certain types of behaviour, which are not an integral part of practice, on the basis that behaving that way will make the world – or the profession – a better place. ‘Do no harm’ is fine. ‘Go away and do good’ is much more problematic.

The BSB Consultation on the Proposed Amendments to the Equality Rules is open until 5pm on Friday 29 November. You can access the full consultation document at tinyurl.com/4xcstb3t and respond at: tinyurl.com/y62jmzye. The BSB has published an FAQ document on the consultation which can be viewed at: tinyurl.com/37mt28ss

Update 20/11/24: The Bar Council published its response to the Equality Rules consultation on 18 November. See also 'BSB Equality Rules amendments proposals are the wrong approach, warns the Bar Council'.

Much has been done by the Bar Council, the Inns, the Circuits, the Legal Practice Management Association and Institute of Barristers’ Clerks, and the Bar Standards Board (BSB), to try to overcome unfairness or discrimination, and to improve diversity at the Bar. The intake to the practising Bar is now broadly reflective of the overall demographic (apart from the fact that women are overrepresented):

© Bar Council

But there remain real challenges with retention and progression. Despite all the efforts of the profession, there are some profoundly disquieting disparities between the earnings of men and women, and white and non-white barristers, even in the early years of practice (so this ongoing, not a historical hangover). Nobody has yet achieved a good analysis of exactly what causes these differences. There are many possible factors which could be at play: unequal prior access to educational opportunities; hours worked; discrimination by clients; unconscious bias in selection processes; people’s pre-existing contacts; and more generally what is sometimes called social or cultural capital. Perhaps there is also some straightforward unlawful discrimination within chambers – though that seems unlikely to be a major factor given the very few established occasions of it happening.

These continuing disparities in the progression of different groups at the Bar has led the BSB to suggest that the Code of Conduct should do more than merely prohibit unlawful discrimination, and should impose on barristers, by way of professional obligation, a positive duty to act in a way that advances equality, diversity and inclusion. This is understandable, and undoubtedly well-intentioned. But it seems to me to be problematic, and I hope the BSB will not proceed with the change.

In our Code of Conduct the ten core duties underpin the entire regulatory framework.

Core Duty 8 says: ‘You must not discriminate unlawfully against any person.’ That restates a legal obligation which applies to us anyway, but it means that regulatory sanctions are readily available for breaching it. It is easy to understand what it means and it is a good duty to have.

The BSB wants to change this to: ‘You must act in a way that advances equality, diversity and inclusion.’ And the BSB also proposes some new Equality Rules to explain what is required.

There is no definition of equality, diversity or inclusion in the present handbook but the BSB’s consultation tells us what it means by these words. Equality means equality of opportunity. Diversity means ‘ensuring that profession is reflective of the population it serves’. Inclusion means ‘creating a respectful environment and culture where people feel valued and are able to participate and reach their full potential’.

The BSB says that compliance with the new Core Duty and Equality Rules ‘is not necessarily to have achieved equality of outcome, but to have taken reasonable steps and to have demonstrated progress over time.’ The BSB’s purpose in making the rule change is ‘to achiev[e] behaviour and cultural change across the profession’.

Making conduct rules is the wrong way to achieve this ambition.

There are practical difficulties because there will inevitably be uncertainty as to what has to be done to satisfy the duty, and how much is enough.

But I think there is a point of principle lurking here too. Is it a proper purpose of a code of conduct to achieve cultural change? Or is the purpose of conduct rules better limited to ensuring that clients are properly served by the professionals in whom they place their trust?

The Code of Conduct is at its heart about maintaining minimum standards for our practice. Those standards ought to be focused on our professional job, which is the privilege of representing our clients without fear or favour, and that is why those minimum standards are set high. The core duties rightly focus on our duties to the court, to our clients, and to the administration of justice.

Is it appropriate for the BSB to impose on barristers a positive duty to promote various features of the profession which are plainly secondary to our core role as barristers, even where what is to be promoted is a desirable social good like equality of opportunity? Is it properly the role of the regulator to compel me, as part of the price of practising, to promote the social goods that the BSB has identified? What if I would prefer to direct that same effort to ensuring my chambers was carbon-neutral? Or to my particular conception of social justice?

It is one thing to legislate or regulate to prevent harm. It is quite another to legislate or regulate to compel certain types of behaviour, which are not an integral part of practice, on the basis that behaving that way will make the world – or the profession – a better place. ‘Do no harm’ is fine. ‘Go away and do good’ is much more problematic.

The BSB Consultation on the Proposed Amendments to the Equality Rules is open until 5pm on Friday 29 November. You can access the full consultation document at tinyurl.com/4xcstb3t and respond at: tinyurl.com/y62jmzye. The BSB has published an FAQ document on the consultation which can be viewed at: tinyurl.com/37mt28ss

Update 20/11/24: The Bar Council published its response to the Equality Rules consultation on 18 November. See also 'BSB Equality Rules amendments proposals are the wrong approach, warns the Bar Council'.

Imposing a professional obligation to act in a way that advances equality, diversity and inclusion is the wrong way to achieve this ambition, says Nick Vineall KC

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar