*/

Desiree Artesi meets Malcolm Bishop KC, the Lord Chief Justice of Tonga, who talks about his new role in the South Pacific and reflects on his career

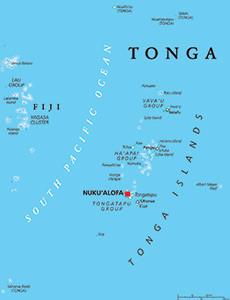

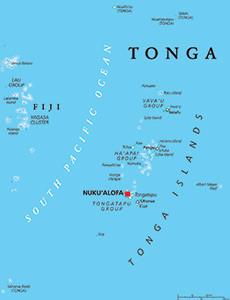

‘Tonga isn’t ageist,’ quips Malcolm Bishop KC. The Welsh silk began his four-year term as Lord Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and President of the Land Court and Court of Appeal of the Kingdom of Tonga in September 2024, at the age of 79, and a month later was celebrating his 80th birthday in the beautiful island country in the southern Pacific Ocean.

As Lord Chief he heads Tonga’s Supreme Court, hearing criminal and civil cases as well as appeals from the Magistrates’ Courts and as President of the Land Court he adjudicates on land ownership disputes. ‘I hope my appointment is taken as some encouragement to those barristers experiencing [career] disappointments,’ Malcolm says.

He had earlier applied to be a counsel to the UK COVID-19 Inquiry: ‘I had a delightful interview but was not accepted on the basis that it was “below my pay grade”. I was a bit disappointed to be told that I was overqualified,’ says the Welsh silk. He is a former deputy High Court judge (Family Division), Crown Court Recorder and Chair of the Commission of Inquiry into the Isle of Man Legal Aid Scheme. ‘But, I said, “fair enough,” and carried on. We all have our ups and downs at the Bar; we win cases, we lose cases, we shrug it off and go on to the next. And that is what I was doing.

‘Then out of the blue, I received an email enquiring whether I would be interested in applying to become Lord Chief Justice. I immediately thought it must be a prank. Funnily enough, it came as a result of a letter I wrote to the Times in support of the barristers’ strike. Someone in Tonga had read this and, a year later, got in touch to invite me to apply along with everyone else.

‘I sought to talk myself out of all the reasons not to apply: the distance, what was the healthcare like, how often can I get to go to the UK etc.? In the end, I decided to apply because I felt qualified for the role. There was a competition. I was interviewed in Singapore and my appointment was approved by His Majesty King Tupou VI in Privy Council.’

Malcolm and I are meeting over video. It is a dark November evening for me but a sunny morning for Malcolm, who has just arrived in Chambers after a gentle, 15-minute chauffeured commute. He is fitting in this interview before his sitting day starts at 10am. The language of the courts is English, except the Magistrates’ Court where the language is Tongan.

How is the role is going so far? ‘It’s extremely enjoyable,’ says Malcolm. He is quick to praise his staff and all the support he receives, though admits to struggling with the formality with which he is treated. He is working on instituting a spirit of collegiality (‘we’re all human beings!’) and reducing unnecessary displays of deference. I suggest he has his work cut out for him and he agrees that much of it is down to cultural traditions.

Any other surprises? Malcolm recounts the first occasion he entered court. The advocates stood, in the usual way, and were not wearing trousers but a tunic (‘tupenus’) which reaches at least the knees and around the waist a ‘táovala’, which is a seaweed woven mat. It is considered very disrespectful to go into court without wearing a táovala.

Court staff are constantly amazed at his ability to deliver ex tempore judgments – ‘one of the tremendous skills that a British trained barrister and judge acquires under our system’. In Tonga, the court associate takes a note of the judgment, prepares it (properly typed up with all corrections) and it is posted on the court website for everyone to read and comment upon. It is therefore not unusual for members of the general public, as well as legal professionals, organisations and government bodies to pass comment on his judgments. ‘On the whole, this is successful,’ Malcolm comments.

The Court of Appeal is comprised of New Zealand and Australian lawyers, so another difference with the UK jurisdiction is that in criminal trials, although juries are not given transcripts of the evidence as they are in New Zealand, judges are expected to repeat the evidence in full when summing up. ‘I am changing that,’ says Malcolm.

In Tonga, defendants have an absolute right to a jury trial in criminal cases but in practice ask for a judge sitting alone. The reason for this, Malcolm has been told, is that the juries invariably return a guilty verdict following extremely short deliberations.

In relation to his role on the specialist Land Court, Malcolm is very ably assisted by a specialist in the practice of the issues that arise in that court.

As Lord Chief he is expected to attend ceremonial functions. These have recently included a service at the Catholic cathedral for Law Week and a remembrance service with wreaths being laid by most of the High Commissioners from the Commonwealth. Since being in post, Malcolm has had the opportunity to meet the Crown Prince.

Another of his duties involves attending legal conferences and seminars in the South Pacific jurisdictions. While attending a legal conference, Malcolm was introduced to the ceremony of kava drinking. ‘I took a sip; didn’t taste very much. They said, “No, no, you must drink the whole coconut full of Kava in one go,” which I did. It had quite an effect, but I don’t think I wholly disgraced myself.’

Tonga is 12,000 miles from the small mining village in North Wales where Malcolm was born and brought up. ‘My family were God-fearing, chapel-going people. I went to Sunday school, grammar school, then went off to Regent’s [Park College], Oxford, where I read theology. I also did Hebrew and Greek and so forth... I thought there must be an easier way of getting a degree and changed to law. I was taught by Richard Buxton, the ‘Law Don’ of Exeter College in those days, and a well-liked tutor.’

He joined the Bar through church connections. ‘Pupillage was found for me by Sir Godfrey Le Quesne. I wanted to practise in Wales, and he arranged for pupillage with Dewi Watkin Powell, a prominent Welsh junior. I was accepted as tenant and practised quite happily in London. Then all the other Welsh barristers in those chambers either became judges or went into the service of government which left me a bit high and dry. There was a small set in Cardiff which was being set up and I was approached to join them and I did. It is now the biggest and most successful set in Wales, 30 Park Place.’

He says there is a lesson here for chambers today – the duty to take on pupils, despite financial pressures and other challenges faced. ‘At the time, there were only six of us barristers, but our then Head of Chambers, Charles Pitchford, decided to take on four pupils, which was a bit of madness. Of those four pupils, two became Circuit judges and two became silks. So, not a bad choice.’

Malcolm recounts his early experiences at the Bar, such as paying 100 guineas for a pupillage and waiting for the unpaid dock brief. We talk about the many differences in the way pupillage is obtained today, mostly for the better, but he cautions vigilance that the changes which attempt to create a level playing field are not circumvented by granting exemptions for those seeking to cross-qualify.

‘Everybody was expected, particularly in their earlier years, to do everything. I prefer that because, for me, there is nothing drearier than doing the same sort of case, week in week out. I enjoyed the variety of different areas of practice. All of this, in the end, stood me in good stead with my present job as Lord Chief Justice – as I had the foresight to do crime, civil, judicial review – and of course, the Land Court.’

As we near the end of the interview, Malcolm remarks: ‘I think Jonathan Sumption hit [the nail] on the head when he said, “The Bar is where the magic is.” You can make more money, and perhaps have a more comfortable life, as a solicitor but the magic is still at the Bar in my view. If you are ambitious, prepared to work hard, be your own boss and plot your own path, the Bar is for you.’

He circles back to his earlier advice about not getting derailed by career disappointments. ‘Who knows, around the corner you may have, as I had, a very pleasant surprise.’

‘Tonga isn’t ageist,’ quips Malcolm Bishop KC. The Welsh silk began his four-year term as Lord Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and President of the Land Court and Court of Appeal of the Kingdom of Tonga in September 2024, at the age of 79, and a month later was celebrating his 80th birthday in the beautiful island country in the southern Pacific Ocean.

As Lord Chief he heads Tonga’s Supreme Court, hearing criminal and civil cases as well as appeals from the Magistrates’ Courts and as President of the Land Court he adjudicates on land ownership disputes. ‘I hope my appointment is taken as some encouragement to those barristers experiencing [career] disappointments,’ Malcolm says.

He had earlier applied to be a counsel to the UK COVID-19 Inquiry: ‘I had a delightful interview but was not accepted on the basis that it was “below my pay grade”. I was a bit disappointed to be told that I was overqualified,’ says the Welsh silk. He is a former deputy High Court judge (Family Division), Crown Court Recorder and Chair of the Commission of Inquiry into the Isle of Man Legal Aid Scheme. ‘But, I said, “fair enough,” and carried on. We all have our ups and downs at the Bar; we win cases, we lose cases, we shrug it off and go on to the next. And that is what I was doing.

‘Then out of the blue, I received an email enquiring whether I would be interested in applying to become Lord Chief Justice. I immediately thought it must be a prank. Funnily enough, it came as a result of a letter I wrote to the Times in support of the barristers’ strike. Someone in Tonga had read this and, a year later, got in touch to invite me to apply along with everyone else.

‘I sought to talk myself out of all the reasons not to apply: the distance, what was the healthcare like, how often can I get to go to the UK etc.? In the end, I decided to apply because I felt qualified for the role. There was a competition. I was interviewed in Singapore and my appointment was approved by His Majesty King Tupou VI in Privy Council.’

Malcolm and I are meeting over video. It is a dark November evening for me but a sunny morning for Malcolm, who has just arrived in Chambers after a gentle, 15-minute chauffeured commute. He is fitting in this interview before his sitting day starts at 10am. The language of the courts is English, except the Magistrates’ Court where the language is Tongan.

How is the role is going so far? ‘It’s extremely enjoyable,’ says Malcolm. He is quick to praise his staff and all the support he receives, though admits to struggling with the formality with which he is treated. He is working on instituting a spirit of collegiality (‘we’re all human beings!’) and reducing unnecessary displays of deference. I suggest he has his work cut out for him and he agrees that much of it is down to cultural traditions.

Any other surprises? Malcolm recounts the first occasion he entered court. The advocates stood, in the usual way, and were not wearing trousers but a tunic (‘tupenus’) which reaches at least the knees and around the waist a ‘táovala’, which is a seaweed woven mat. It is considered very disrespectful to go into court without wearing a táovala.

Court staff are constantly amazed at his ability to deliver ex tempore judgments – ‘one of the tremendous skills that a British trained barrister and judge acquires under our system’. In Tonga, the court associate takes a note of the judgment, prepares it (properly typed up with all corrections) and it is posted on the court website for everyone to read and comment upon. It is therefore not unusual for members of the general public, as well as legal professionals, organisations and government bodies to pass comment on his judgments. ‘On the whole, this is successful,’ Malcolm comments.

The Court of Appeal is comprised of New Zealand and Australian lawyers, so another difference with the UK jurisdiction is that in criminal trials, although juries are not given transcripts of the evidence as they are in New Zealand, judges are expected to repeat the evidence in full when summing up. ‘I am changing that,’ says Malcolm.

In Tonga, defendants have an absolute right to a jury trial in criminal cases but in practice ask for a judge sitting alone. The reason for this, Malcolm has been told, is that the juries invariably return a guilty verdict following extremely short deliberations.

In relation to his role on the specialist Land Court, Malcolm is very ably assisted by a specialist in the practice of the issues that arise in that court.

As Lord Chief he is expected to attend ceremonial functions. These have recently included a service at the Catholic cathedral for Law Week and a remembrance service with wreaths being laid by most of the High Commissioners from the Commonwealth. Since being in post, Malcolm has had the opportunity to meet the Crown Prince.

Another of his duties involves attending legal conferences and seminars in the South Pacific jurisdictions. While attending a legal conference, Malcolm was introduced to the ceremony of kava drinking. ‘I took a sip; didn’t taste very much. They said, “No, no, you must drink the whole coconut full of Kava in one go,” which I did. It had quite an effect, but I don’t think I wholly disgraced myself.’

Tonga is 12,000 miles from the small mining village in North Wales where Malcolm was born and brought up. ‘My family were God-fearing, chapel-going people. I went to Sunday school, grammar school, then went off to Regent’s [Park College], Oxford, where I read theology. I also did Hebrew and Greek and so forth... I thought there must be an easier way of getting a degree and changed to law. I was taught by Richard Buxton, the ‘Law Don’ of Exeter College in those days, and a well-liked tutor.’

He joined the Bar through church connections. ‘Pupillage was found for me by Sir Godfrey Le Quesne. I wanted to practise in Wales, and he arranged for pupillage with Dewi Watkin Powell, a prominent Welsh junior. I was accepted as tenant and practised quite happily in London. Then all the other Welsh barristers in those chambers either became judges or went into the service of government which left me a bit high and dry. There was a small set in Cardiff which was being set up and I was approached to join them and I did. It is now the biggest and most successful set in Wales, 30 Park Place.’

He says there is a lesson here for chambers today – the duty to take on pupils, despite financial pressures and other challenges faced. ‘At the time, there were only six of us barristers, but our then Head of Chambers, Charles Pitchford, decided to take on four pupils, which was a bit of madness. Of those four pupils, two became Circuit judges and two became silks. So, not a bad choice.’

Malcolm recounts his early experiences at the Bar, such as paying 100 guineas for a pupillage and waiting for the unpaid dock brief. We talk about the many differences in the way pupillage is obtained today, mostly for the better, but he cautions vigilance that the changes which attempt to create a level playing field are not circumvented by granting exemptions for those seeking to cross-qualify.

‘Everybody was expected, particularly in their earlier years, to do everything. I prefer that because, for me, there is nothing drearier than doing the same sort of case, week in week out. I enjoyed the variety of different areas of practice. All of this, in the end, stood me in good stead with my present job as Lord Chief Justice – as I had the foresight to do crime, civil, judicial review – and of course, the Land Court.’

As we near the end of the interview, Malcolm remarks: ‘I think Jonathan Sumption hit [the nail] on the head when he said, “The Bar is where the magic is.” You can make more money, and perhaps have a more comfortable life, as a solicitor but the magic is still at the Bar in my view. If you are ambitious, prepared to work hard, be your own boss and plot your own path, the Bar is for you.’

He circles back to his earlier advice about not getting derailed by career disappointments. ‘Who knows, around the corner you may have, as I had, a very pleasant surprise.’

Desiree Artesi meets Malcolm Bishop KC, the Lord Chief Justice of Tonga, who talks about his new role in the South Pacific and reflects on his career

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar