*/

Jeremy Barnett and David Ormerod CBE KC (Hon) explore the emerging technologies and principles at stake

In a recent paper, a number of academics who specialise in ‘LawTech’ from the UK, the USA, Canada, Australia and Singapore joined together to warn of the dangers to the rule of law by the use of artificial intelligence (AI) by the courts, tribunals and judiciary. JudicialTech supporting justice, published in October 2023, considered whether computers can/should replace judges. The paper examined the trial process in sections: litigation advice, trial preparation, judicial guidance, pretrial negotiations, digital courts/tribunals and judicial algorithms. It went on to explain the core technology and main risks around the provision of a validated and accurate dataset, transparency and bias.

The advantages identified include access to justice specifically with reference to the speed of preparation and reduction of the court backlog, fairness where there is great potential to ‘level the playing field’, especially for litigants in person, and audit – in particular the identification of any deepfake legal submissions and judicial bias.

However, public confidence could be eroded if judicial decisions are made by algorithms. AI litigation advice systems (see box, below) may mean even fewer civil cases will come to trial, adversely impacting the evolution of common law. There is also the risk that algorithmic judicial decisions will be wrong/unfair and may require an automatic right of appeal in every case to a human judge, and AI algorithms are not currently subject to professional auditing and regulation.

On a broader view, across the justice system controversial issues surround recidivism algorithms (used to assess a defendant’s likelihood of committing future crime), sentencing algorithms and computer programs used to predict risk and determine prison terms. Fully automated algorithms are the subject of extensive debate, with many having high error rates, opaque design and a demonstrable racial bias.

The authors’ conclusion was that the introduction of new technology in any application to the judicial process needs to be controlled by the judiciary to maintain public confidence in the legal system and rule of law. No one is denying that there is clear scope for judges to use emerging technology to support their decision-making and to create efficiency savings, which in turn can promote access to justice. However, claims that algorithmic decision-making is ‘better’ in terms of reduced bias and increased transparency are premature and risk eroding fundamental principles. In short, judicial decisions are so heavily context dependent and responsive to the needs and circumstances of parties that they should be made by experienced experts – human judges.

A further concern is that judges may be skeptical as to the capabilities of AI technology. There may be resistance from those whose lack of understanding of the AI capacities leads them to see AI as nothing more than an evil threat. Some may be anxious about the impact on their future careers. But above all, for a great many judges, lawyers, academics and court users, there will be the deeper-seated concern that the independence of the judiciary may be eroded by the use of machines to decide important matters that have always been regarded as within the province of the judge. It is for this reason that the authors make a clear distinction between ‘judicial support tools’ which are to be encouraged and judicial ‘decision-making tools’ which are to be resisted at all costs.

Having identified the arguments for judicial control and caution, the authors are now engaged in analysing the practical application of the techniques that were identified. One stream of work relates to criminal trials in our main jurisdictions (England, USA, Canada, Australia and Singapore) where similar issues arise despite the different legal codes in each jurisdiction.

In the criminal law context, there are substantial opportunities for judicial support tools. One example, which makes crystal clear the distinction from judicial decision-making, is in relation to sentencing. We have proposed a judicial sentencing tool which assists the judge, expeditiously and efficiently, to identify the appropriate sentence range and essential matters to be included in sentencing remarks. This can offer significant benefits in alleviating the burden on the judge in any sentencing exercise with consequent savings on that precious and expensive judicial resource.

Such a tool can help maximise the likelihood of sentence consistency and the importance that like cases are treated alike. Such a system which goes no further than identifying likely sentencing ranges and sketching out appropriate matters for inclusion in sentencing remarks supports the judge without trespassing on their decision-making power. That stands in stark contrast with a system which seeks to replace the judicial decision-making power by stipulating the sentence to be imposed.

The aim of this next phase of work is therefore to design a suite of tools that assist judges to prepare and work through their heavy daily court lists, while ensuring that the essential ingredient of judicial decision-making is preserved. Sentencing is one example of many under consideration where it is possible to identify tasks where immediate benefits can be identified, to assist judges in assimilating large data sets in ‘short order’. (One obvious dataset is the body of Court of Appeal sentencing decisions appropriate to the case.) Substantial research and development is required to understand how the benefits of such a system can be delivered.

In due course, the authors will consider the feasibility of other judicial support tools such as previous routes to verdict and legal directions which have been endorsed by the senior judiciary in conviction appeals.

The principal recommendation of the 2023 paper was that to protect the rule of law, there should be a presumption against the use of judicial decision-making algorithms in conventional criminal and civil litigation unless the technology has completed a robust appraisal and testing regime which must be supervised by the judiciary.

The issue of auditing AI systems is rapidly becoming of great importance. Attempts have already been made to insist on independent auditing of AI systems by computer scientists who would impose their own definitions of bias. The authors are clear that if confidence in the rule of law is to be maintained, it is essential that the judiciary plays a proactive role in the use of the technology in trials and must have the sole responsibility to audit any AI systems used in criminal trials.

**

This article is based JudicialTech supporting justice (October 2023), which Jeremy Barnett co-authored with Fredric Lederer, Chancellor Professor of Law and Director of the Center for Legal and Court Technology and Legal Skills at William & Mary Law School, a former prosecutor, defence counsel, trial judge, court reform expert and pioneer of virtual courts; Philip Treleaven, Professor of Computer Science at University College of London who is credited with coining the term RegTech and whose research group 25 years ago developed much of the early financial fraud detection technology and built the first insider dealing detection system for the London Stock Exchange; Nicholas Vermeys, Professor at the Université de Montréal, Director of the Centre de recherche en droit public (CRDP), Associate Director of the Cyberjustice Laboratory and a member of the Quebec Bar; and John Zeleznikow, Professor of Law and Technology at La Trobe University in Australia who pioneered the use of Machine Learning and Game theory to enhance legal decision-making.

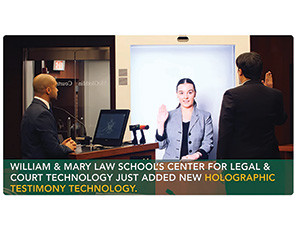

The US Center for Legal & Court Technology maintains in William & Mary Law School what is described as the world’s most technologically advanced trial and appellate courtroom, including full hybrid operation that permits 3D life-size Holographic remote appearances and AI-based automatic speech to text transcript. See the technology on William & Mary’s YouTube channeland read more in ‘Beam me up, counselor. Are hologram witnesses headed to court?’ Karen Sloan, Reuters, 16 May 2023.

In a recent paper, a number of academics who specialise in ‘LawTech’ from the UK, the USA, Canada, Australia and Singapore joined together to warn of the dangers to the rule of law by the use of artificial intelligence (AI) by the courts, tribunals and judiciary. JudicialTech supporting justice, published in October 2023, considered whether computers can/should replace judges. The paper examined the trial process in sections: litigation advice, trial preparation, judicial guidance, pretrial negotiations, digital courts/tribunals and judicial algorithms. It went on to explain the core technology and main risks around the provision of a validated and accurate dataset, transparency and bias.

The advantages identified include access to justice specifically with reference to the speed of preparation and reduction of the court backlog, fairness where there is great potential to ‘level the playing field’, especially for litigants in person, and audit – in particular the identification of any deepfake legal submissions and judicial bias.

However, public confidence could be eroded if judicial decisions are made by algorithms. AI litigation advice systems (see box, below) may mean even fewer civil cases will come to trial, adversely impacting the evolution of common law. There is also the risk that algorithmic judicial decisions will be wrong/unfair and may require an automatic right of appeal in every case to a human judge, and AI algorithms are not currently subject to professional auditing and regulation.

On a broader view, across the justice system controversial issues surround recidivism algorithms (used to assess a defendant’s likelihood of committing future crime), sentencing algorithms and computer programs used to predict risk and determine prison terms. Fully automated algorithms are the subject of extensive debate, with many having high error rates, opaque design and a demonstrable racial bias.

The authors’ conclusion was that the introduction of new technology in any application to the judicial process needs to be controlled by the judiciary to maintain public confidence in the legal system and rule of law. No one is denying that there is clear scope for judges to use emerging technology to support their decision-making and to create efficiency savings, which in turn can promote access to justice. However, claims that algorithmic decision-making is ‘better’ in terms of reduced bias and increased transparency are premature and risk eroding fundamental principles. In short, judicial decisions are so heavily context dependent and responsive to the needs and circumstances of parties that they should be made by experienced experts – human judges.

A further concern is that judges may be skeptical as to the capabilities of AI technology. There may be resistance from those whose lack of understanding of the AI capacities leads them to see AI as nothing more than an evil threat. Some may be anxious about the impact on their future careers. But above all, for a great many judges, lawyers, academics and court users, there will be the deeper-seated concern that the independence of the judiciary may be eroded by the use of machines to decide important matters that have always been regarded as within the province of the judge. It is for this reason that the authors make a clear distinction between ‘judicial support tools’ which are to be encouraged and judicial ‘decision-making tools’ which are to be resisted at all costs.

Having identified the arguments for judicial control and caution, the authors are now engaged in analysing the practical application of the techniques that were identified. One stream of work relates to criminal trials in our main jurisdictions (England, USA, Canada, Australia and Singapore) where similar issues arise despite the different legal codes in each jurisdiction.

In the criminal law context, there are substantial opportunities for judicial support tools. One example, which makes crystal clear the distinction from judicial decision-making, is in relation to sentencing. We have proposed a judicial sentencing tool which assists the judge, expeditiously and efficiently, to identify the appropriate sentence range and essential matters to be included in sentencing remarks. This can offer significant benefits in alleviating the burden on the judge in any sentencing exercise with consequent savings on that precious and expensive judicial resource.

Such a tool can help maximise the likelihood of sentence consistency and the importance that like cases are treated alike. Such a system which goes no further than identifying likely sentencing ranges and sketching out appropriate matters for inclusion in sentencing remarks supports the judge without trespassing on their decision-making power. That stands in stark contrast with a system which seeks to replace the judicial decision-making power by stipulating the sentence to be imposed.

The aim of this next phase of work is therefore to design a suite of tools that assist judges to prepare and work through their heavy daily court lists, while ensuring that the essential ingredient of judicial decision-making is preserved. Sentencing is one example of many under consideration where it is possible to identify tasks where immediate benefits can be identified, to assist judges in assimilating large data sets in ‘short order’. (One obvious dataset is the body of Court of Appeal sentencing decisions appropriate to the case.) Substantial research and development is required to understand how the benefits of such a system can be delivered.

In due course, the authors will consider the feasibility of other judicial support tools such as previous routes to verdict and legal directions which have been endorsed by the senior judiciary in conviction appeals.

The principal recommendation of the 2023 paper was that to protect the rule of law, there should be a presumption against the use of judicial decision-making algorithms in conventional criminal and civil litigation unless the technology has completed a robust appraisal and testing regime which must be supervised by the judiciary.

The issue of auditing AI systems is rapidly becoming of great importance. Attempts have already been made to insist on independent auditing of AI systems by computer scientists who would impose their own definitions of bias. The authors are clear that if confidence in the rule of law is to be maintained, it is essential that the judiciary plays a proactive role in the use of the technology in trials and must have the sole responsibility to audit any AI systems used in criminal trials.

**

This article is based JudicialTech supporting justice (October 2023), which Jeremy Barnett co-authored with Fredric Lederer, Chancellor Professor of Law and Director of the Center for Legal and Court Technology and Legal Skills at William & Mary Law School, a former prosecutor, defence counsel, trial judge, court reform expert and pioneer of virtual courts; Philip Treleaven, Professor of Computer Science at University College of London who is credited with coining the term RegTech and whose research group 25 years ago developed much of the early financial fraud detection technology and built the first insider dealing detection system for the London Stock Exchange; Nicholas Vermeys, Professor at the Université de Montréal, Director of the Centre de recherche en droit public (CRDP), Associate Director of the Cyberjustice Laboratory and a member of the Quebec Bar; and John Zeleznikow, Professor of Law and Technology at La Trobe University in Australia who pioneered the use of Machine Learning and Game theory to enhance legal decision-making.

The US Center for Legal & Court Technology maintains in William & Mary Law School what is described as the world’s most technologically advanced trial and appellate courtroom, including full hybrid operation that permits 3D life-size Holographic remote appearances and AI-based automatic speech to text transcript. See the technology on William & Mary’s YouTube channeland read more in ‘Beam me up, counselor. Are hologram witnesses headed to court?’ Karen Sloan, Reuters, 16 May 2023.

Jeremy Barnett and David Ormerod CBE KC (Hon) explore the emerging technologies and principles at stake

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar