*/

From a ‘difficult woman with attitude’ to a ‘rainmaker’ – Paramjit Ahluwalia talks about her experience of intersectionality at the Bar, examines the data on disparity of earnings and presents the potential for change

‘Intersectionality’, the conceptual term formulated by Professor of Law Kimberle Crenshaw, describes how characteristics such as race, class and gender can overlap and intersect to create multiple forms of inequality that compound and create obstacles.

This article focuses on the intersection of race and gender at the Bar and examines the earnings of ethnicity sub-sets both at the self-employed Bar as a whole and at the criminal Bar. By looking at this sensitive issue through a constructive and business-minded lens, I aim to show how we can find solutions.

*

At one of my first pupillage interviews, I was asked: ‘What’s a nice Asian girl like you wanting to practise at the criminal Bar for?’ I completed pupillage elsewhere in a different area of law. On being refused tenancy there, I was told by my supervisor: ‘The thing is, you’re just not academic enough to be a barrister. You’ll never write articles, you’re not the sort to write chapters in books and you’re just not the type of person to appear before the Court of Appeal.’ I believed him. So, weighed with student debt in one hand and an Oxford University degree in the other, I took a job in Birmingham – thinking it best to leave the Bar entirely. I did go back, trying two 3rd six pupillages in crime (and still not taking the hint). I finally secured tenancy under the leadership of the late and great Francis Gilbert, head of chambers at Mitre House. Before Chambers finally closed its doors, I was taught an important lesson – under the right leadership and in the right cultural environment, any individual can thrive on merit and hard work alone at the Bar.

In Race at the Bar: three years on, published in December 2024, the Bar Council analysed progress made since its seminal 2021 report. It found that ‘in all areas of practice, and at all stages of career from young Bar to silk, Black and Asian barristers continued to earn less than their White colleagues’.

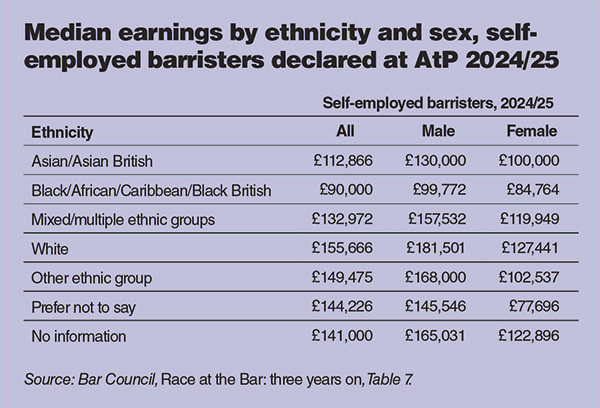

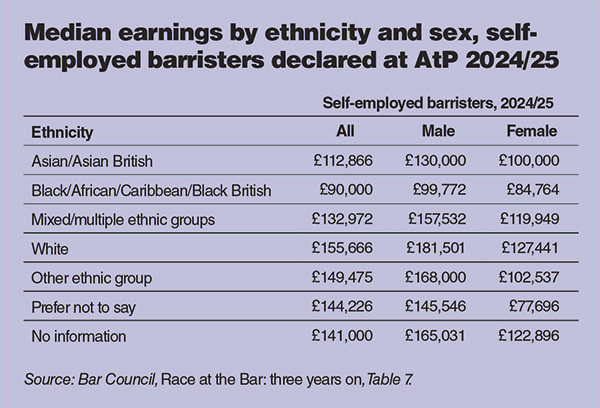

With earnings data sourced from Authorisation to Practise forms for 2024-25, the report showed how the impact of gender compounds the impact of ethnicity. Median earnings for self-employed barristers within all practice areas were found to be £181,501 for the sub-set of White men. In comparison, White women earned 70% of that amount; Asian men 72%; Asian women 55%; Black men 55%; and Black women 47%. There was some disparity found at the employed Bar, but not to this level.

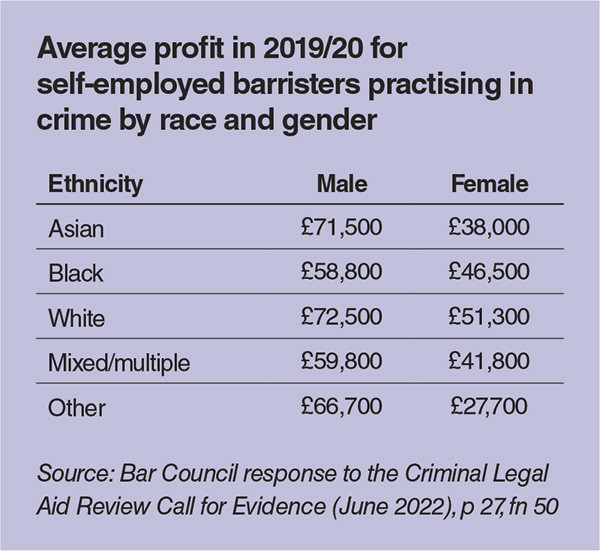

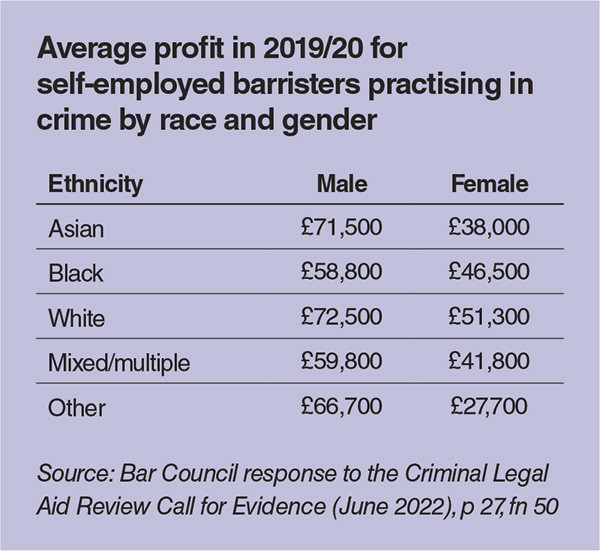

The Bar Council has undertaken to expand its work programme on earnings/work distribution by sex to include race. Meanwhile, the most recently published intersectional data relating to individuals practising in crime is found in the Bar Council response to the Criminal Legal Aid Review Call for Evidence (June 2022). This shows average profit in 2019/20 was £71,500 for Asian men and £38,000 for Asian women. For Black men it was £58,800 and Black women £46,500. For White men it was £72,500 and White women £51,300. Mixed/multiple ethnicities men earned an average profit of £59,800 compared to mixed/multiple ethnicities women at £41,800. Even using regression models to isolate race and gender, the Bar Council’s figures showed that in criminal practice, Asian women earned £16,400 a year less, and Black women earned £18,700 less, than White men.

The Bar Council’s Barristers’ Working Lives Survey 2023 found that 28% of Asian women and 28% of Black women did not believe work was distributed fairly in their chambers (compared to 13% of overall respondents and 8% of White men). Further, the survey report revealed that 60.7% of Asian women; 75.5% of Black women and 54.1% of women from mixed/multiple backgrounds had personally experienced bullying, harassment or discrimination at work in the previous two years. The top reason cited for not reporting was fear of repercussions.

The Bar Council’s 2024 Race at the Bar report observed:

Women, those of colour and younger barristers are more likely to experience bullying, harassment, and discrimination at work. Those complained about are usually in positions of power – judges, senior barristers, senior clerks, and practice managers.

Among the 2024 report’s many recommendations was that:

Chambers and organisations sincere about embedding anti-racism as part of their operations must take a deeper look at cultures of racism and structural inequalities that persist.

In my view, disparity of earnings data not only provides potential reasons for, but much more importantly, solutions to the issue of retention and progression at the Bar of ethnic minority women.

I nearly had to leave the Bar in my mid-30s, on account of low earnings in comparison to other individuals of my experience practising in crime. When I tried to raise this issue internally, I was labelled as a ‘difficult woman with attitude’ (among other choice words). In the background, I had to make a stark decision on whether to continue in practice at the Bar and took a £30,000 bank loan to be able to do so. I felt a complete failure, barely surviving in my profession let alone thriving.

All of us at the Bar, including the clerking profession, have urgent choices to make together. Brushing things under the carpet, gaslighting or dismissing evidence of disparities as ‘woke’ are simply not viable solutions if we want to operate within an efficient, sustainable and profitable business system.

The first step is the hardest – accepting there is a problem. To ‘fix’ the problem I am not suggesting superficial marketing, nor victimhood status; but taking practical and strategic action, based on meritocracy and with a growth mindset.

At no point am I suggesting that median figures for the highest earning sub-sets (such as Asian men or White men) ever be considered or utilised as a divisive tactic. Instead, we should see these as a guideline demonstrating what any individual’s practice can grow to, in the right supportive environment and with hard work. Some chambers have, perhaps in the past, operated like fiefdoms, with strict power dynamics and hierarchy. Step or speak out of line with the ‘powers that be’ and who knows what little work you might have/what work you might lose. Such a style of management, in my opinion, promotes business stagnancy.

Times are fast-changing and there are many talented individuals in the clerking profession who are business-minded and progressive; who know that real success for a chambers comes out of valuing and developing ‘human capital’ – their barrister members. For example, if one part of your workforce has much lower output than another of similar skillset and experience, then the profitability of chambers is not reaching its full potential. Inadvertently, this can create structural weaknesses for the future, with barristers poached by other chambers or leaving the profession entirely.

So, what’s the answer? To listen and proactively support each individual barrister in their career and allow them to reach their full potential and growth without fear, stereotypes or defensiveness. By retaining the best talent and increasing profits into your chambers, every single member of chambers benefits, regardless of background.

Importantly, there is real impetus for change from our leadership at the Bar. In her inaugural address as 2025 Chair of the Bar, Barbara Mills KC said:

Addressing earnings disparities must be at the top of our agenda, especially at the junior end of the profession – earnings in early years can set a trajectory for an entire career.

The Bar Chair went on to highlight the need to support barristers from underrepresented groups, particularly at the young Bar. While one group of young barristers she met on a Circuit visit were not aware of the Bar Council’s report on new practitioner earnings and toolkits for ‘meaningful’ practice reviews, another group told her they found practice and income reviews ‘impossible to deal with’. Mills said that work is under way to raise awareness of such tools and resources to the whole Bar including the incorporation of practice management and reviews into new practitioner programmes.

So, for individuals who perhaps, like me, have experienced a beautifully imperfect and scenic career pathway at the Bar – whatever stage you are at – don’t give up hope; don’t pack up your wig and gown; instead, prove the doubters wrong and become the rainmakers of tomorrow.

Race at the Bar: three years on, Bar Council, December 2024.

Barristers’ Working Lives 2023 Report, Bar Council, October 2024.

Bar Council Response to the Criminal Legal Aid Review Call for Evidence, June 2022.

Barbara Mills KC, Chair of the Bar’s inaugural address, 8 January 2025.

New practitioner earnings differentials, Bar Council, April 2024.

See also ‘Managing your practice as a junior barrister’, Counsel December 2023: Michael Harwood explains the ‘what, when, and how’ of practice reviews for those looking to take more control over the direction of their practice.

‘Race at the Bar – three years on’, Counsel January 2025: Mariam Diaby interviews Laurie-Anne Power KC, Jason Pitter KC, Harpreet Sandhu KC, Eleena Misra KC and Simon Regis CBE who reflect on progress made as well as the persistent challenges and cultural shifts still needed.

‘Intersectionality’, the conceptual term formulated by Professor of Law Kimberle Crenshaw, describes how characteristics such as race, class and gender can overlap and intersect to create multiple forms of inequality that compound and create obstacles.

This article focuses on the intersection of race and gender at the Bar and examines the earnings of ethnicity sub-sets both at the self-employed Bar as a whole and at the criminal Bar. By looking at this sensitive issue through a constructive and business-minded lens, I aim to show how we can find solutions.

*

At one of my first pupillage interviews, I was asked: ‘What’s a nice Asian girl like you wanting to practise at the criminal Bar for?’ I completed pupillage elsewhere in a different area of law. On being refused tenancy there, I was told by my supervisor: ‘The thing is, you’re just not academic enough to be a barrister. You’ll never write articles, you’re not the sort to write chapters in books and you’re just not the type of person to appear before the Court of Appeal.’ I believed him. So, weighed with student debt in one hand and an Oxford University degree in the other, I took a job in Birmingham – thinking it best to leave the Bar entirely. I did go back, trying two 3rd six pupillages in crime (and still not taking the hint). I finally secured tenancy under the leadership of the late and great Francis Gilbert, head of chambers at Mitre House. Before Chambers finally closed its doors, I was taught an important lesson – under the right leadership and in the right cultural environment, any individual can thrive on merit and hard work alone at the Bar.

In Race at the Bar: three years on, published in December 2024, the Bar Council analysed progress made since its seminal 2021 report. It found that ‘in all areas of practice, and at all stages of career from young Bar to silk, Black and Asian barristers continued to earn less than their White colleagues’.

With earnings data sourced from Authorisation to Practise forms for 2024-25, the report showed how the impact of gender compounds the impact of ethnicity. Median earnings for self-employed barristers within all practice areas were found to be £181,501 for the sub-set of White men. In comparison, White women earned 70% of that amount; Asian men 72%; Asian women 55%; Black men 55%; and Black women 47%. There was some disparity found at the employed Bar, but not to this level.

The Bar Council has undertaken to expand its work programme on earnings/work distribution by sex to include race. Meanwhile, the most recently published intersectional data relating to individuals practising in crime is found in the Bar Council response to the Criminal Legal Aid Review Call for Evidence (June 2022). This shows average profit in 2019/20 was £71,500 for Asian men and £38,000 for Asian women. For Black men it was £58,800 and Black women £46,500. For White men it was £72,500 and White women £51,300. Mixed/multiple ethnicities men earned an average profit of £59,800 compared to mixed/multiple ethnicities women at £41,800. Even using regression models to isolate race and gender, the Bar Council’s figures showed that in criminal practice, Asian women earned £16,400 a year less, and Black women earned £18,700 less, than White men.

The Bar Council’s Barristers’ Working Lives Survey 2023 found that 28% of Asian women and 28% of Black women did not believe work was distributed fairly in their chambers (compared to 13% of overall respondents and 8% of White men). Further, the survey report revealed that 60.7% of Asian women; 75.5% of Black women and 54.1% of women from mixed/multiple backgrounds had personally experienced bullying, harassment or discrimination at work in the previous two years. The top reason cited for not reporting was fear of repercussions.

The Bar Council’s 2024 Race at the Bar report observed:

Women, those of colour and younger barristers are more likely to experience bullying, harassment, and discrimination at work. Those complained about are usually in positions of power – judges, senior barristers, senior clerks, and practice managers.

Among the 2024 report’s many recommendations was that:

Chambers and organisations sincere about embedding anti-racism as part of their operations must take a deeper look at cultures of racism and structural inequalities that persist.

In my view, disparity of earnings data not only provides potential reasons for, but much more importantly, solutions to the issue of retention and progression at the Bar of ethnic minority women.

I nearly had to leave the Bar in my mid-30s, on account of low earnings in comparison to other individuals of my experience practising in crime. When I tried to raise this issue internally, I was labelled as a ‘difficult woman with attitude’ (among other choice words). In the background, I had to make a stark decision on whether to continue in practice at the Bar and took a £30,000 bank loan to be able to do so. I felt a complete failure, barely surviving in my profession let alone thriving.

All of us at the Bar, including the clerking profession, have urgent choices to make together. Brushing things under the carpet, gaslighting or dismissing evidence of disparities as ‘woke’ are simply not viable solutions if we want to operate within an efficient, sustainable and profitable business system.

The first step is the hardest – accepting there is a problem. To ‘fix’ the problem I am not suggesting superficial marketing, nor victimhood status; but taking practical and strategic action, based on meritocracy and with a growth mindset.

At no point am I suggesting that median figures for the highest earning sub-sets (such as Asian men or White men) ever be considered or utilised as a divisive tactic. Instead, we should see these as a guideline demonstrating what any individual’s practice can grow to, in the right supportive environment and with hard work. Some chambers have, perhaps in the past, operated like fiefdoms, with strict power dynamics and hierarchy. Step or speak out of line with the ‘powers that be’ and who knows what little work you might have/what work you might lose. Such a style of management, in my opinion, promotes business stagnancy.

Times are fast-changing and there are many talented individuals in the clerking profession who are business-minded and progressive; who know that real success for a chambers comes out of valuing and developing ‘human capital’ – their barrister members. For example, if one part of your workforce has much lower output than another of similar skillset and experience, then the profitability of chambers is not reaching its full potential. Inadvertently, this can create structural weaknesses for the future, with barristers poached by other chambers or leaving the profession entirely.

So, what’s the answer? To listen and proactively support each individual barrister in their career and allow them to reach their full potential and growth without fear, stereotypes or defensiveness. By retaining the best talent and increasing profits into your chambers, every single member of chambers benefits, regardless of background.

Importantly, there is real impetus for change from our leadership at the Bar. In her inaugural address as 2025 Chair of the Bar, Barbara Mills KC said:

Addressing earnings disparities must be at the top of our agenda, especially at the junior end of the profession – earnings in early years can set a trajectory for an entire career.

The Bar Chair went on to highlight the need to support barristers from underrepresented groups, particularly at the young Bar. While one group of young barristers she met on a Circuit visit were not aware of the Bar Council’s report on new practitioner earnings and toolkits for ‘meaningful’ practice reviews, another group told her they found practice and income reviews ‘impossible to deal with’. Mills said that work is under way to raise awareness of such tools and resources to the whole Bar including the incorporation of practice management and reviews into new practitioner programmes.

So, for individuals who perhaps, like me, have experienced a beautifully imperfect and scenic career pathway at the Bar – whatever stage you are at – don’t give up hope; don’t pack up your wig and gown; instead, prove the doubters wrong and become the rainmakers of tomorrow.

Race at the Bar: three years on, Bar Council, December 2024.

Barristers’ Working Lives 2023 Report, Bar Council, October 2024.

Bar Council Response to the Criminal Legal Aid Review Call for Evidence, June 2022.

Barbara Mills KC, Chair of the Bar’s inaugural address, 8 January 2025.

New practitioner earnings differentials, Bar Council, April 2024.

See also ‘Managing your practice as a junior barrister’, Counsel December 2023: Michael Harwood explains the ‘what, when, and how’ of practice reviews for those looking to take more control over the direction of their practice.

‘Race at the Bar – three years on’, Counsel January 2025: Mariam Diaby interviews Laurie-Anne Power KC, Jason Pitter KC, Harpreet Sandhu KC, Eleena Misra KC and Simon Regis CBE who reflect on progress made as well as the persistent challenges and cultural shifts still needed.

From a ‘difficult woman with attitude’ to a ‘rainmaker’ – Paramjit Ahluwalia talks about her experience of intersectionality at the Bar, examines the data on disparity of earnings and presents the potential for change

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar