*/

Most social mobility programs are targeted too late to be effective. There, I have said it. It’s a sweeping statement, and no doubt some of you have already started typing eloquent re-buffs, but please hear me out.

If we look at most of the great schemes aiming to open the legal profession to lower socio-economic groups, we see a common theme. They are aimed at those in the later stages of their postgraduate legal training or, often, university level. Is this the right stage to be targeting? I am going to argue that it is too late. Too late to make any significant difference.

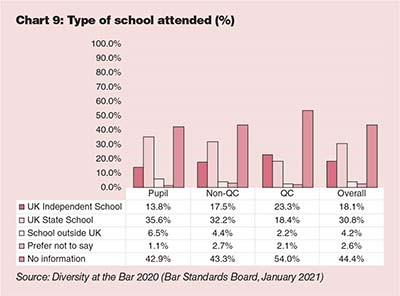

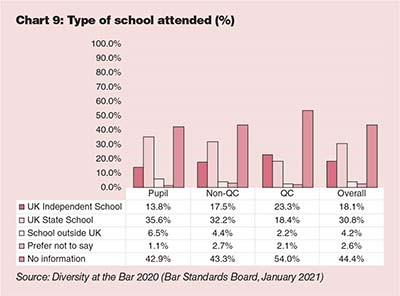

The table below, taken from Diversity at the Bar 2020 (Bar Standards Board, January 2021), demonstrates what I mean. Of those who responded to the question on type of school attended, 18.1% said they came from independent schools and 30.8% from a state school. This compares with 7% of children having attended an independent school in England (6.5% in the UK) (Independent Schools Council, 2021).

What is also interesting is the low rate of response: 44.4%. Even if all those who chose not to respond to this question happened to be state-school educated, the proportion of barristers who went to independent schools would still be disproportionately higher than in the wider population.

If we look to alternative sources, the Sutton Trust published its first report on the educational backgrounds of the UK’s professional elite over a decade ago. This researched the schools and universities attended by barristers, judges, solicitors and other sectors. Since then, it has published over ten updates, the latest of which (in 2016) noted the ‘staying-power of the privately-educated at the top’ and that even when those with such backgrounds retire from the top of their field, ‘they are frequently replaced by those with a similar educational past’ (Leading People, Sutton Trust/Philip Kirby).

The Sutton Trust/Kirby study showed that 71% of barristers, and 74% of judges, attended independent schools – compared with 7% of the UK population; 78% of barristers, and 74% of judges, attended Oxbridge – compared with under 1% of the UK population. Whichever way we look at it, this is a highly significant deviation from the wider population. Furthermore, the Bar and judiciary (along with the military at 71%) top the list of sectors dominated by independent-school education; medicine follows at 61%; journalism is 51%; solicitors 51%; politics (Cabinet) 50%; Civil Service 48%; and business 34%.

Then think about this, how many of those who attend state school actually come from higher socio-economic groups? According to a 2019 article in the Guardian, 40% of children from families with income in excess of £300,000 p/a go to state schools (Britain’s private school problem: it’s time to talk, Francis Green and David Kynaston, The Guardian 13 January 2019). Currently, this is something as a profession we are less focused on, but is this masking yet further issues with our recruitment?

To assess progress in social mobility more accurately, the Sutton Trust’s Social Mobility Toolkit 2021 recommends looking at four areas in this order:

Interestingly, though, we concentrate our social mobility efforts, in the main, well after this stage. If I had not come from a working-class background, I might be using stable door and horse analogies here!

It is not radical to suggest we need to engage with potential entrants before they start studying for their legal qualifications; before they go to university; and before they sit their A-Levels.

An effective social mobility policy needs to start in secondary schools. Children can only opt to study for a career as a barrister if they know about it. They need to be shown what a great career option it can be, and that it is open to people like them. They need to know what A-Level options to choose. They need to know about funding sources that will enable them to shoulder the massive financial training burden. Only by engaging with children earlier will we ever start to succeed in our ambitions for social mobility. All other attempts will be akin to sticking a sandbag in the door as the dam breaks.

Most social mobility programs are targeted too late to be effective. There, I have said it. It’s a sweeping statement, and no doubt some of you have already started typing eloquent re-buffs, but please hear me out.

If we look at most of the great schemes aiming to open the legal profession to lower socio-economic groups, we see a common theme. They are aimed at those in the later stages of their postgraduate legal training or, often, university level. Is this the right stage to be targeting? I am going to argue that it is too late. Too late to make any significant difference.

The table below, taken from Diversity at the Bar 2020 (Bar Standards Board, January 2021), demonstrates what I mean. Of those who responded to the question on type of school attended, 18.1% said they came from independent schools and 30.8% from a state school. This compares with 7% of children having attended an independent school in England (6.5% in the UK) (Independent Schools Council, 2021).

What is also interesting is the low rate of response: 44.4%. Even if all those who chose not to respond to this question happened to be state-school educated, the proportion of barristers who went to independent schools would still be disproportionately higher than in the wider population.

If we look to alternative sources, the Sutton Trust published its first report on the educational backgrounds of the UK’s professional elite over a decade ago. This researched the schools and universities attended by barristers, judges, solicitors and other sectors. Since then, it has published over ten updates, the latest of which (in 2016) noted the ‘staying-power of the privately-educated at the top’ and that even when those with such backgrounds retire from the top of their field, ‘they are frequently replaced by those with a similar educational past’ (Leading People, Sutton Trust/Philip Kirby).

The Sutton Trust/Kirby study showed that 71% of barristers, and 74% of judges, attended independent schools – compared with 7% of the UK population; 78% of barristers, and 74% of judges, attended Oxbridge – compared with under 1% of the UK population. Whichever way we look at it, this is a highly significant deviation from the wider population. Furthermore, the Bar and judiciary (along with the military at 71%) top the list of sectors dominated by independent-school education; medicine follows at 61%; journalism is 51%; solicitors 51%; politics (Cabinet) 50%; Civil Service 48%; and business 34%.

Then think about this, how many of those who attend state school actually come from higher socio-economic groups? According to a 2019 article in the Guardian, 40% of children from families with income in excess of £300,000 p/a go to state schools (Britain’s private school problem: it’s time to talk, Francis Green and David Kynaston, The Guardian 13 January 2019). Currently, this is something as a profession we are less focused on, but is this masking yet further issues with our recruitment?

To assess progress in social mobility more accurately, the Sutton Trust’s Social Mobility Toolkit 2021 recommends looking at four areas in this order:

Interestingly, though, we concentrate our social mobility efforts, in the main, well after this stage. If I had not come from a working-class background, I might be using stable door and horse analogies here!

It is not radical to suggest we need to engage with potential entrants before they start studying for their legal qualifications; before they go to university; and before they sit their A-Levels.

An effective social mobility policy needs to start in secondary schools. Children can only opt to study for a career as a barrister if they know about it. They need to be shown what a great career option it can be, and that it is open to people like them. They need to know what A-Level options to choose. They need to know about funding sources that will enable them to shoulder the massive financial training burden. Only by engaging with children earlier will we ever start to succeed in our ambitions for social mobility. All other attempts will be akin to sticking a sandbag in the door as the dam breaks.

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar